High Profit Margins Don't Justify High Stock Valuations

Why today’s elevated stock market valuations must reflect expectations about the future, not record profitability

The stock market is once again trading at levels that make investors uneasy. AI enthusiasm has pushed a handful of firms to extraordinary heights, and the major indexes have followed. Whenever valuations climb this far, a familiar debate returns. Are stocks overvalued or have we entered a new equilibrium where a more profitable corporate sector justifies today’s lofty valuations? A closer look suggests that one of the most common justifications for high stock prices rests on a basic misunderstanding of how valuation multiples work.

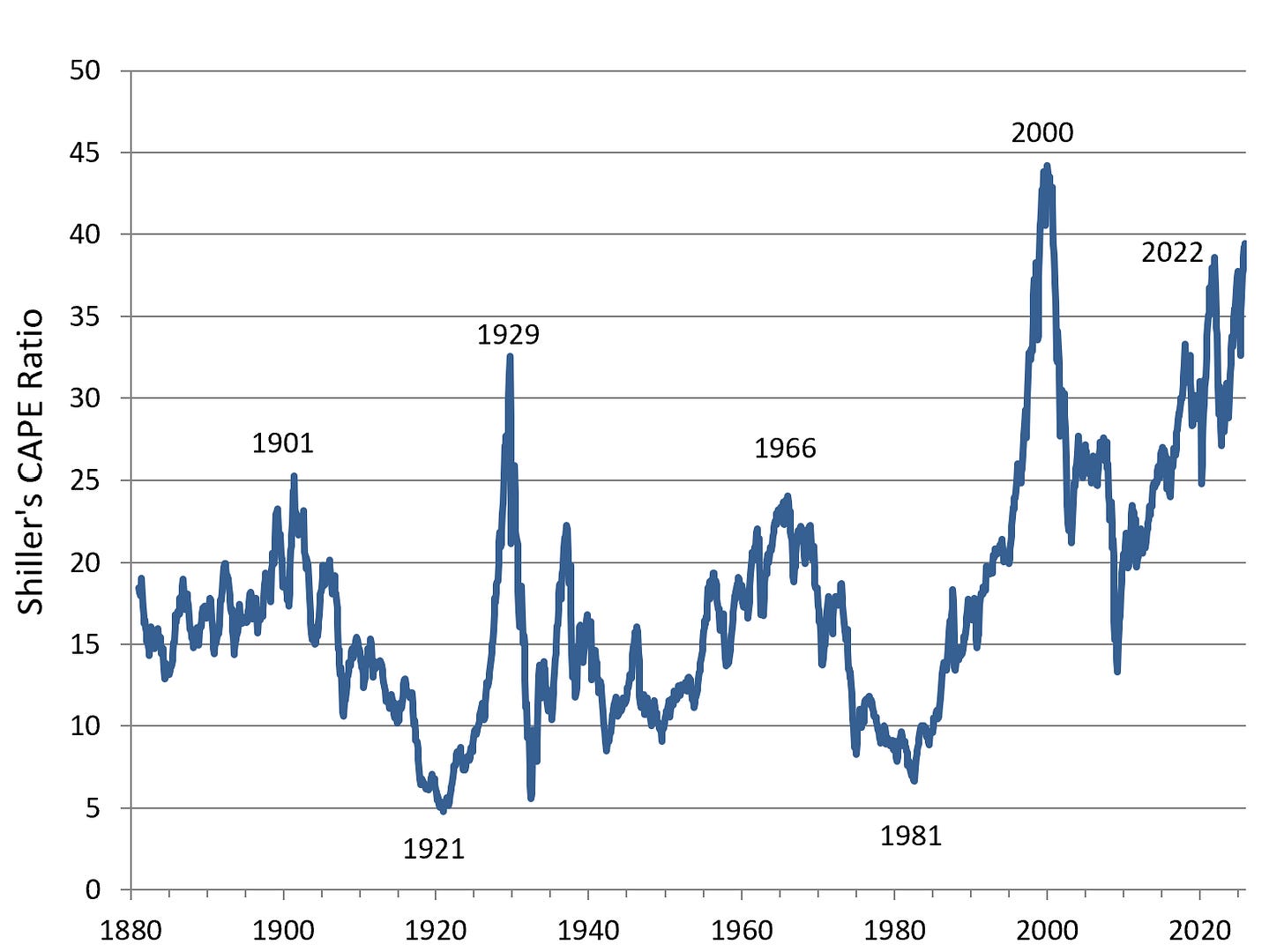

To put today’s market in context, Figure 1 shows that the current CAPE ratio of about 40—Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio, which smooths earnings over the business cycle—has only been matched once in the last century and a half. And that occurred during the height of the dot-com bubble.

Many market observers are quick to dismiss any discussion of the market being overvalued based on multiples like the CAPE ratio. They point to the fact that while a near-record high CAPE ratio may be a sign that valuations are indeed currently stretched, timing a market exit based on this metric has caused many investors to miss out on major run-ups in stock prices.

Once this point has been made, the next argument usually goes something like this:

Firms today are far more profitable than they were in the past, which justifies today’s near-record-high multiples.

Unfortunately, this argument is fundamentally flawed. A firm with higher profit margins produces more earnings for every dollar of sales. Holding prices (P) constant, higher profit margins raise earnings (E), which mechanically leads to a lower P/E ratio, not a higher one. Investors may then bid up the stock price if they believe the margin gains (and therefore higher earnings) will persist. As the price rises, the P/E ratio moves back toward its previous level. In this simple equilibrium, prices rise just enough to reflect higher earnings, leaving the P/E ratio essentially unchanged.

High profit margins explain why earnings are high. They do not explain why investors should pay more per dollar of earnings.

To justify a higher P/E ratio, higher margins must signal higher expected earnings growth or lower perceived riskiness of the firm’s cash flows, or both. Margins by themselves are not enough.

For example, if higher margins reflect a new, durable competitive advantage that will persist for many years, then the expected growth rate of future earnings rises. A higher growth rate increases the present value of the firm, which supports a higher price today and, thus a higher P/E ratio.

Alternatively, if higher margins suggest that future cash flows are less risky, investors may require a lower return to hold the stock. A lower discount rate increases the present value of a firm, which leads to a higher price today and, therefore a higher valuation multiple.

In both cases the justification for a higher P/E ratio lies in long run assumptions about growth or risk, not in the firm’s current margins.

This distinction becomes especially important in the AI era. The firms at the center of the current boom have remarkable profit margins (e.g., Nvidia), and some have plausible paths to even greater profitability as AI becomes embedded in their ecosystems. Investors may reasonably believe that these competitive advantages will create a durable moat into the future. They may also believe that AI will lead to higher earnings growth for many years. If so, today’s high valuation multiples could be justified. But the justification hinges on very strong assumptions about the future. It does not follow from record-high margins alone.

Once the margin narrative is removed, the valuation question becomes much sharper. The stock market is clearly expensive by historical standards. To defend these valuations, one must rely on bold claims about the long run impact of AI or the persistence of dominant platforms in the digital economy. Those arguments may turn out to be correct. But they should be stated plainly, not hidden behind the argument that firms are more profitable than they ever were in the past.

The bottom line is simple. If today’s near-record valuations prove justified, it will be because investors are right about the future path of earnings and risk, not because today’s dominant firms happen to earn unusually high margins.

If you enjoyed this mildly efficient and occasionally rational debunking of the margin myth, consider subscribing below. We’ll keep exploring markets and models, uncovering mildly surprising truths along the way.

No hot takes; just thoughtful ones.

About the Author: Seth Neumuller is an Associate Professor of Economics at Wellesley College where he teaches and conducts research in macroeconomics and finance. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from UCLA. His Substack is Mildly Efficient (and Occasionally Rational) where he explores topics in finance and macro from first principles, cutting through complexity with clear, grounded analysis.

Notes and Sources

AI tools were used to edit prose; all figures are straightforward to reproduce from the cited sources.