Is the AI Capex Boom Financially Sustainable?

How shrinking financial slack and long-dated leases underpin Nvidia’s current valuation

TL;DR

Hyperscalers can keep expanding AI infrastructure, but only with shrinking financial slack. All are increasingly relying on long-dated leases that push the funding constraint into the future. At Oracle, operating cash flow no longer covers AI investment, making this shift a necessity rather than a choice. Nvidia’s valuation assumes AI demand grows fast enough to sustain a capital-intensive, lease-backed expansion.

Introduction

Over the past several years, the hyperscalers, including Microsoft, Alphabet, Meta, and Oracle, have embarked on one of the most aggressive infrastructure buildouts in modern corporate history. Collectively, these firms are now investing well over $200 billion per year in new data centers equipped with advanced semiconductors, networking equipment, and even on-site power generation to meet current and anticipated demand for AI model training and inference.

For Nvidia, this spending wave is not merely a tailwind for revenue growth. Its current valuation depends critically on the ability and willingness of the hyperscalers to continue expanding AI infrastructure investment for many years to come.

Nvidia itself has been explicit about how concentrated this demand is. In its most recent quarterly filing, the company notes that “our revenue is concentrated among a limited number of direct, indirect and cloud service purchasers,” and discloses that four direct customers each accounted for more than 10% of quarterly revenue.

This raises a fundamental question. Is the current pace of AI infrastructure investment by the hyperscalers financially sustainable? And if not, what does that imply for Nvidia’s current valuation?

Answering this question requires looking beyond headline financial metrics and focusing on how investments in AI infrastructure are actually being funded.

Measuring sustainability

Periods of rapid capital accumulation tend to distort conventional financial metrics, particularly headline free cash flow. Free cash flow often compresses at times like this as large investment outlays occur now while the cash flows they are expected to generate arrive much later. In such cases, free cash flow blends operating performance, investment intensity, and financing choices, making it a poor guide to whether current investment levels are financially sustainable.

Changes in cash balances are similarly uninformative in this environment, since firms can preserve cash by shifting investment into leases, reducing share buybacks, or raising funds through debt and other external financing, even as underlying funding slack erodes.

To evaluate sustainability, I instead focus on how much internally generated cash remains once AI infrastructure investment has been accounted for, and how quickly that margin is shrinking. This is summarized by the funding coverage ratio, which I define as follows:

Funding coverage ratio = Adjusted operating cash flow ÷ AI infrastructure investment

AI infrastructure investment is measured as capital expenditures plus finance lease principal payments, treating owned and leased assets symmetrically. Adjusted operating cash flow (Adjusted CFO) is cash flow from operations net of stock-based compensation, which removes equity-financed labor costs and isolates the cash actually available to fund investment.

This decomposition isolates the core sustainability question of the AI capex boom: how much operating cash remains after funding infrastructure, and how quickly it is being exhausted as investment continues to scale.

A funding coverage ratio above one indicates that a firm is able to fund investment internally out of operating cash flow. A ratio below one implies reliance on external financing through debt, leases, or other balance-sheet commitments. But even if the ratio is above one, a sustained decline signals diminishing financial slack as investment absorbs an increasing share of internally generated cash.

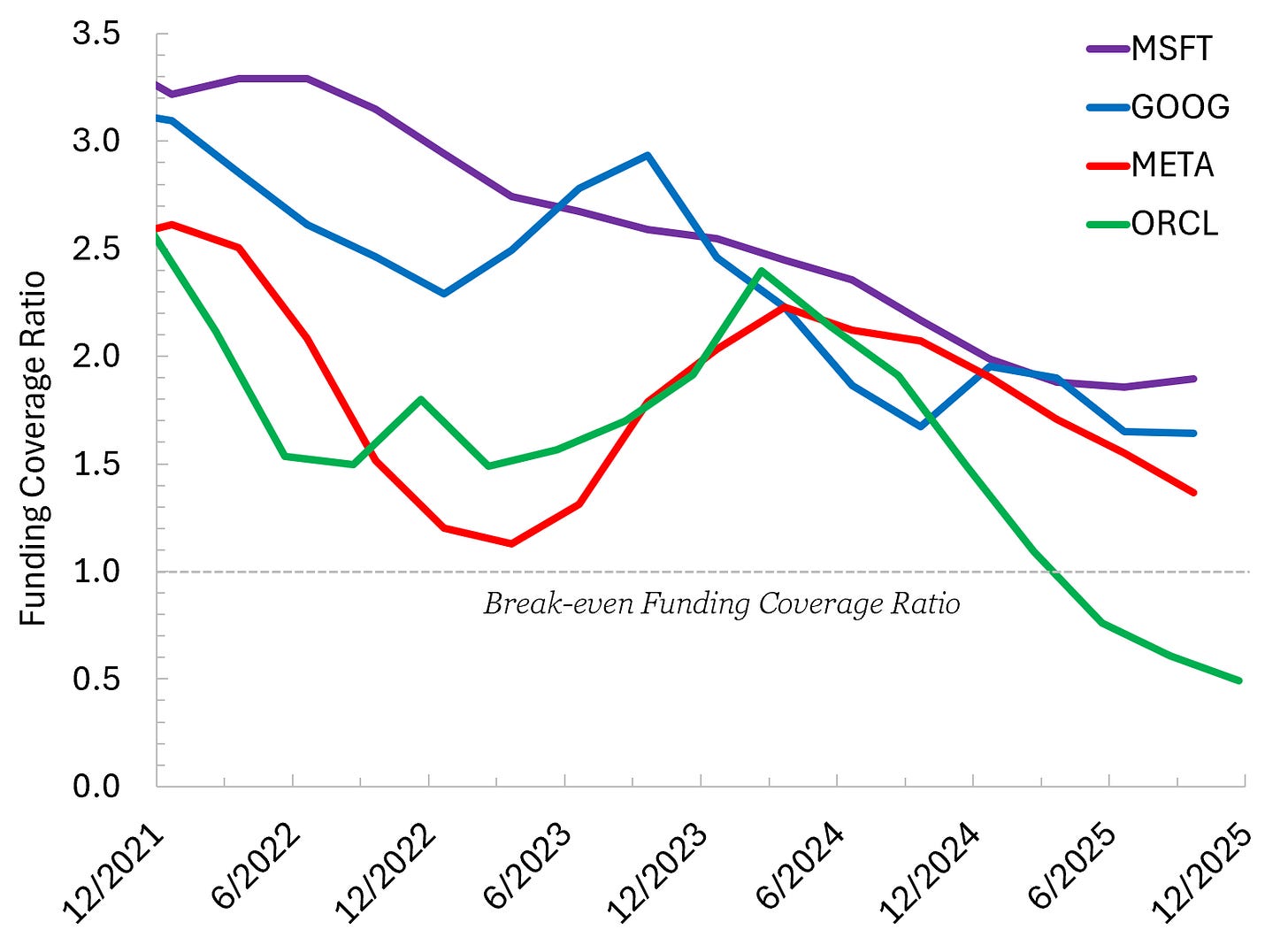

Figure 1 depicts the funding coverage ratio since late 2021 for Microsoft, Alphabet, Meta, and Oracle.

The broad pattern is clear. Microsoft, Alphabet, and Meta are currently able to fund investment internally, but they are doing so with materially less slack than just a few years ago. The AI infrastructure buildout has increasingly become the dominant use of internally generated funds.

Oracle’s funding coverage ratio is notably different. As of May 2025, it fell below one and has continued to decline, indicating that the company can no longer fund AI infrastructure investments internally. For Oracle, continuing to invest in AI infrastructure during the back half of 2025 required turning to external financing, both via debt markets and long-dated lease commitments.

While Microsoft, Alphabet, and Meta remain above the break-even threshold, their steady convergence toward it suggests that Oracle may not be an outlier, but a preview of what lies ahead if the AI infrastructure buildout continues at its current torrid pace (or accelerates further).

In the next section, I explore in more detail how these hyperscalers are adjusting their approach in response to declining excess cash from operations.

How hyperscalers are adjusting as funding slack erodes

As Figure 1 shows, AI infrastructure investment is absorbing a steadily growing share of internally generated cash flow. As funding slack erodes, how are hyperscalers adjusting in practice?

At Alphabet and Meta, the primary margin of adjustment has been share repurchases. Both firms remain internally funded on a cash basis, but only by allowing buybacks to absorb the pressure created by rising AI capex. As funding coverage ratios decline, discretionary uses of cash become the buffer that preserves balance-sheet stability. The result is fewer dollars returned to shareholders in order to sustain the infrastructure buildout.

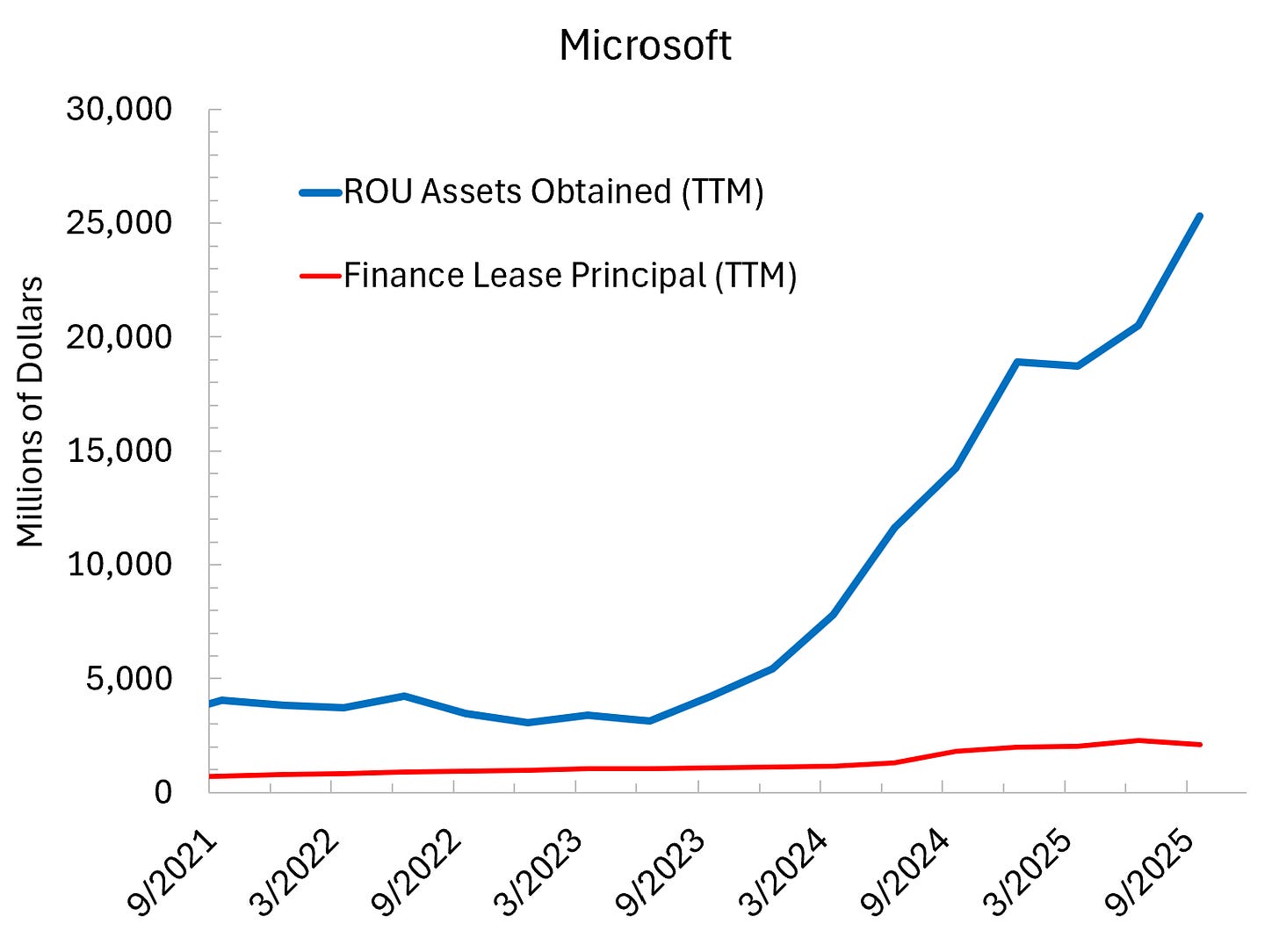

On a pure cash-flow basis, Microsoft continues to generate ample operating cash relative to current AI investment. But this apparent slack increasingly reflects the timing of cash outlays rather than the absence of commitments. As I will demonstrate in the following section, a growing share of Microsoft’s AI buildout is being financed by long-dated leases that defer cash payments while locking in compute capacity today.

Oracle gives us a view into how hyperscalers respond when financial constraints start to bind. With a funding coverage ratio now well below one, the company no longer generates enough operating cash to fund AI infrastructure investment internally. Continued expansion has therefore required reliance on external financing, including debt issuance and long-dated lease commitments to secure compute capacity. The recent decline in Oracle’s stock price is consistent with growing investor concern about whether the company’s AI infrastructure buildout is financially sustainable going forward.

Despite differences in financial strength, the hyperscalers’ responses point to a common adjustment process. As internal funding capacity tightens, firms first reduce discretionary cash uses (e.g., share repurchases) and then shift toward external financing (e.g., debt and long-dated leases) that push cash outlays into the future. The AI buildout continues, but increasingly because hyperscalers are changing how it is paid for, not because internal cash generation is keeping pace with capex growth.

The growing importance of long-dated leases

As internal funding slack erodes, hyperscalers have increasingly relied on long-dated leases to sustain the pace of AI infrastructure investment. These arrangements span both finance and operating leases.

Finance leases are best understood as deferred capital expenditures financed over time. The lessee bears the economic risks and rewards of ownership, often with a purchase option that is reasonably certain to be exercised. Thus, finance leases are economically equivalent to purchasing infrastructure with borrowed funds, which is why finance lease principal payments are included alongside capex when assessing the sustainability of AI investment.

In contrast, operating leases transfer some risk away from hyperscalers onto data center owners since hyperscalers do not own the infrastructure but instead are committing to rent space within the data center itself.

While these structures differ in accounting treatment and risk allocation, their economic effect is similar.

Microsoft was the earliest and most visible adopter of this approach. Figure 2 shows a sharp rise in right-of-use (ROU) assets obtained via leases beginning in 2023, while cash principal payments associated with these agreements have increased much more gradually. The gap reflects a growing stock of future obligations that are not yet flowing through to today’s operating cash flow.

Recent disclosures indicate that this approach is spreading across the hyperscalers. In its most recent 10-Q filing, Alphabet reported tens of billions of dollars in data center lease commitments not yet reflected on its balance sheet, with terms extending well into the next decade.

Meta reports a similarly large pipeline of lease commitments, disclosing approximately $58 billion in leases that have not yet commenced, largely related to data centers, with payments scheduled to begin over the remainder of this decade.

Oracle’s disclosures are larger still, reaching into the hundreds of billions of dollars, reflecting the fact that leases have become the primary mechanism allowing the firm to continue expanding AI capacity despite binding constraints on operating cash flow.

More broadly, long-dated leases help explain how the AI infrastructure buildout can continue even as internal funding capacity tightens. They make the buildout more sustainable on the margin by deferring cash outlays today at the cost of increasing fixed claims on future operating cash flows. In effect, hyperscalers are betting that AI demand will materialize at sufficient scale before the bills come due to service the lease commitments being layered onto their balance sheets.

What this means for Nvidia’s current valuation

The shift toward long-dated leases explains how the AI infrastructure buildout can continue even as hyperscalers’ internal funding capacity tightens. By deferring large cash outlays, leases push the binding constraint from today’s operating cash flow to tomorrow’s realized demand for AI compute.

This makes the buildout more sustainable on the margin, but only by replacing liquidity risk with commitment risk. Discretionary capital spending is converted into fixed claims on future operating cash flows, leaving hyperscalers increasingly reliant on AI workloads generating sufficient revenue to justify those obligations over time.

Nvidia’s valuation implicitly assumes that this shift succeeds. That AI demand grows fast enough to service the expanding stock of long-dated commitments now being layered onto hyperscaler balance sheets in response to tightening financial constraints. Given Nvidia’s customer concentration, hyperscaler funding constraints are not peripheral; they are central to the firm’s current valuation.

The analysis above suggests that while the AI capex boom may be sustainable in the near term, it ultimately represents a bet on whether demand for AI compute grows into the capital structure now being built to support it.

If you enjoyed this mildly efficient and occasionally rational look at the sustainability of the AI infrastructure buildout, consider subscribing below. We’ll keep exploring markets and models, uncovering mildly surprising truths along the way.

No hot takes; just thoughtful ones.

About the Author: Seth Neumuller is an Associate Professor of Economics at Wellesley College where he teaches and conducts research in macroeconomics and finance. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from UCLA. His Substack is Mildly Efficient (and Occasionally Rational) where he explores topics in finance and macro from first principles, cutting through complexity with clear, grounded analysis.

Notes and Sources

AI tools were used to edit prose; all figures are straightforward to reproduce from the cited sources.