The Paradox of a Strong Labor Market

Why today’s rising unemployment rate reflects confidence, not contraction

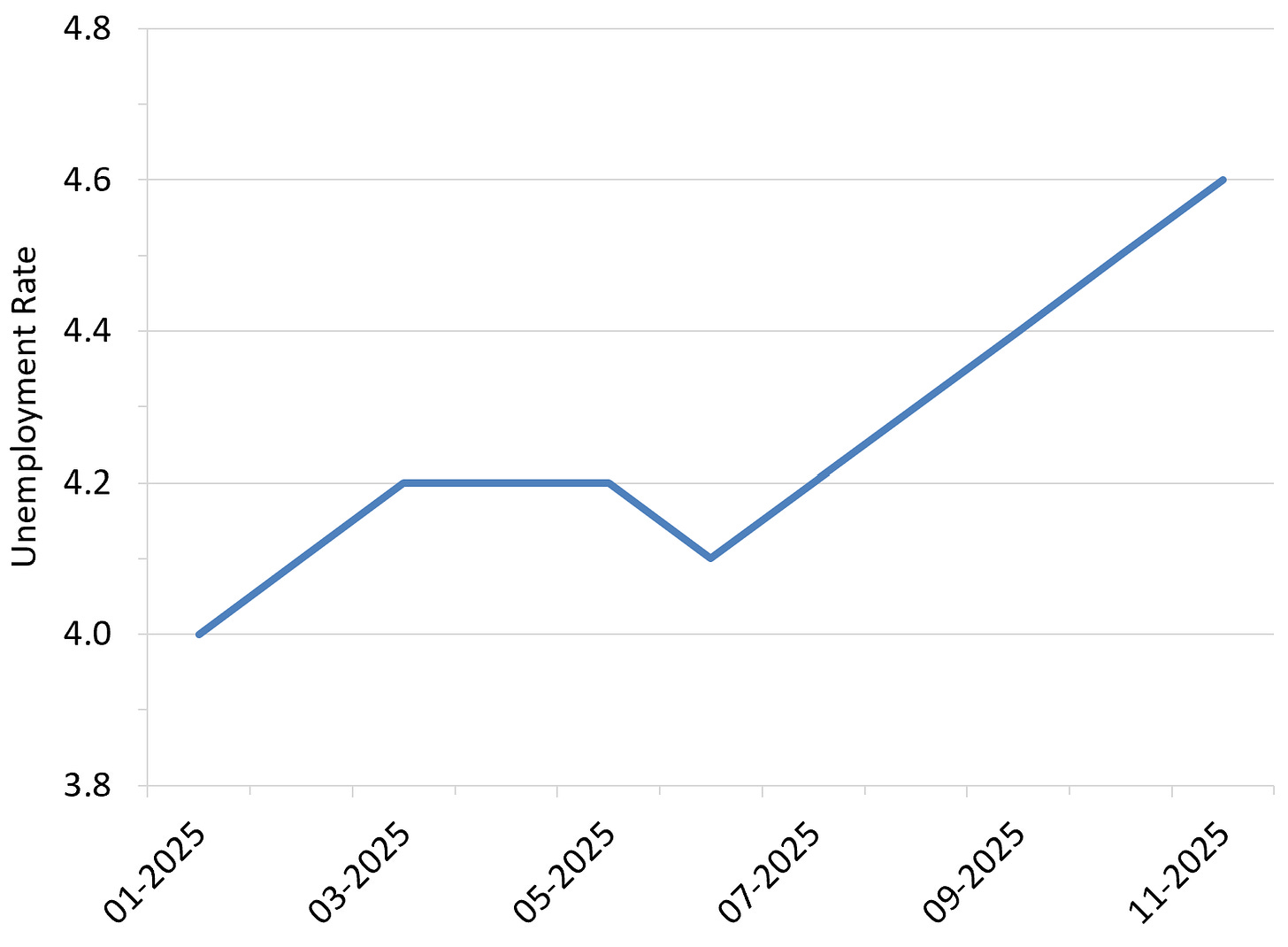

At first glance, the main takeaway from the most recent Employment Situation Summary from the Bureau of Labor Statistics seems straightforward: the unemployment rate has risen from 4.0% in January to 4.6% in November. Many readers will naturally interpret this increase as evidence that the labor market is weakening and that recession risks may be rising. But is that conclusion actually warranted?

To answer that question, it is useful to step back and recall what the unemployment rate actually measures. The unemployment rate is the ratio of unemployed workers to the total size of the labor force, where the labor force is defined as the sum of employed and unemployed workers:

Unemployment rate = Unemployed / (Employed + Unemployed)

This matters because changes in the unemployment rate can arise for very different reasons. An increase could reflect widespread job losses, a surge in new job seekers, or some combination of the two.

Figures 2 and 3 show how the number of employed and unemployed people have changed since the start of the year.

Between January and November, the number of unemployed people increased by roughly 980,000. Over the same period, the number of employed people fell by only about 150,000. Taken together, these two facts make clear that the rise in unemployment cannot be explained simply by workers moving from employment into unemployment.

So what is going on? How can the number of unemployed people rise by far more than the number of employed people falls?

The answer is that the size of the labor force itself must have increased. In other words, a large number of people who were previously neither working nor actively looking for work must have decided to enter the labor market.

As shown in Figure 4, the civilian labor force grew by approximately 830,000 people between January and November. This figure is not an estimate or a model-based inference. It follows directly from the accounting identity that the labor force equals employment plus unemployment: 980,000 more unemployed workers minus 150,000 fewer employed workers implies 830,000 new labor force entrants.

Viewed through this lens, the recent rise in the unemployment rate takes on a very different interpretation. It was driven almost entirely by an influx of new job seekers, not by a collapse in employment.

As a general rule, people do not enter the labor market and begin actively searching for work unless they believe their chances of finding a job are reasonably good. Job search is time-consuming, mentally exhausting, and often financially costly. While some individuals may be pushed into the labor market by necessity, changes in labor force participation at the margin tend to be pro-cyclical: people are more likely to look for work when jobs are plentiful and hiring conditions are favorable.

The increase in the labor force over the past year therefore suggests that the labor market remains relatively strong. Workers appear confident enough in job prospects to step off the sidelines, even if not all of them are immediately successful in securing employment.

To sum up, breaking the unemployment rate into its underlying components tells a very different story than the headline number alone. The rise in the unemployment rate since the start of the year is not a sign that the labor market is rolling over. Paradoxically, it reflects continued labor market strength, as more people are willing to enter the job market and actively compete for available positions.

For investors, the key takeaway is that a rising unemployment rate driven by labor force expansion carries very different implications than one driven by job losses. Historically, recessions and major earnings downturns are associated with sharp declines in employment, not with large inflows of new job seekers. When unemployment rises because more workers are confident enough to look for jobs, it typically signals ongoing economic momentum rather than an imminent contraction. Investors who react mechanically to higher unemployment readings risk mistaking a healthy, expanding labor market for a weakening one and mispricing recession risk.

A sharper policy implication follows directly from this distinction. From the Fed’s perspective, an unemployment rate rising for “good” reasons, all else equal, provides less justification for rapid or aggressive easing.

If you enjoyed this mildly efficient and occasionally rational look at the recent rise in the unemployment rate, consider subscribing below. We’ll keep exploring markets and models, uncovering mildly surprising truths.

No hot takes; just thoughtful ones.

About the Author: Seth Neumuller is an Associate Professor of Economics at Wellesley College where he teaches and conducts research in macroeconomics and finance. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from UCLA. His Substack is Mildly Efficient (and Occasionally Rational) where he explores topics in finance and macro from first principles, cutting through complexity with clear, grounded analysis.

Notes and Sources

AI tools were used to edit prose; all figures are straightforward to reproduce from the cited sources.