Big Tech Is Becoming an Infrastructure Business

What AI Investment Means for Capital Allocation and Valuation

For most of the past two decades, Big Tech’s defining economic feature was not growth, scale, or even profitability. It was how little physical capital these firms required to generate enormous cash flows. Google, Meta, and Microsoft built some of the most valuable businesses in history while remaining fundamentally asset-light. Cash accumulated faster than it could be reinvested, balance sheets stayed flexible, and free cash flow was both abundant and durable.

That model is beginning to change.

The rise of large-scale AI has introduced a very different production process. Training and deploying frontier models requires massive upfront investment in physical infrastructure: data centers with specialized chips, networking equipment, and in some cases dedicated power generation. What were once primarily software businesses are increasingly becoming infrastructure businesses. Unlike earlier cloud build-outs, these investments are both larger in scale and more technologically specific, tying future returns more tightly to sustained demand for AI compute.

This shift is already visible on the balance sheets of Big Tech. The goal of this piece is not to make the case for whether AI investment will ultimately succeed or fail, nor is it to make a near-term valuation call. It is simply to document the transition of Big Tech from asset-light to asset-heavy firms and to explore the implications of this transition for valuing these businesses going forward.

The Surge in Fixed Capital Investment

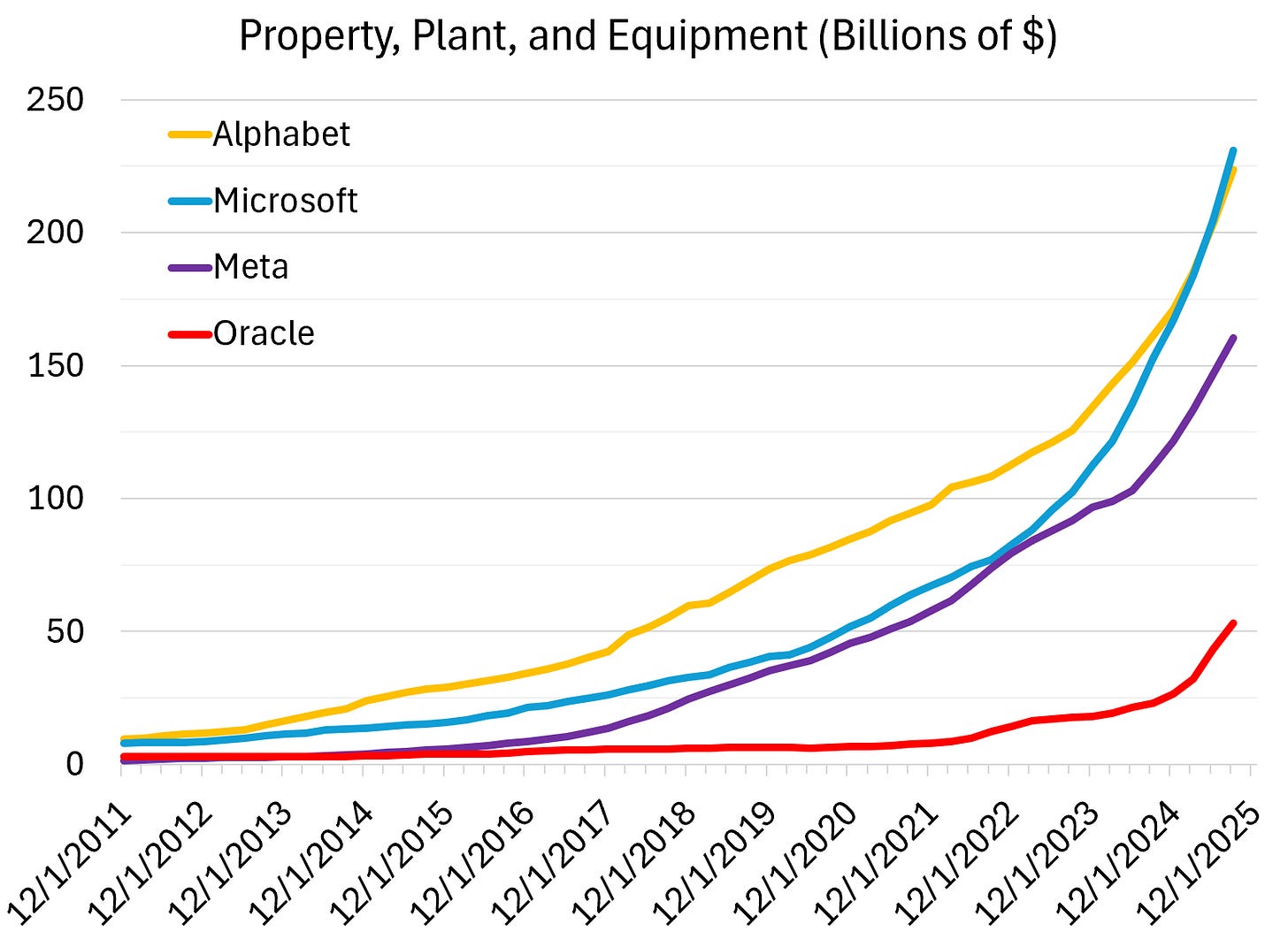

Figure 1 plots Property, Plant, and Equipment (PPE) for Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta, and Oracle since 2011. For all four firms, PPE has risen steadily over time. What stands out is the acceleration beginning around 2019, which intensified further over the past several years.

This is not incremental investment. It is a step change in how these businesses operate.

Alphabet and Microsoft now report well over $200 billion in PPE. Meta, which historically required relatively little physical capital, has seen PPE rise sharply as it builds out AI and data center capacity. Oracle also shows a meaningful increase as it expands its cloud infrastructure and positions itself as a provider of AI compute capacity.

Rising levels of PPE alone, however, do not tell us whether this investment reflects a deeper shift in business models or simply physical capital scaling alongside revenue.

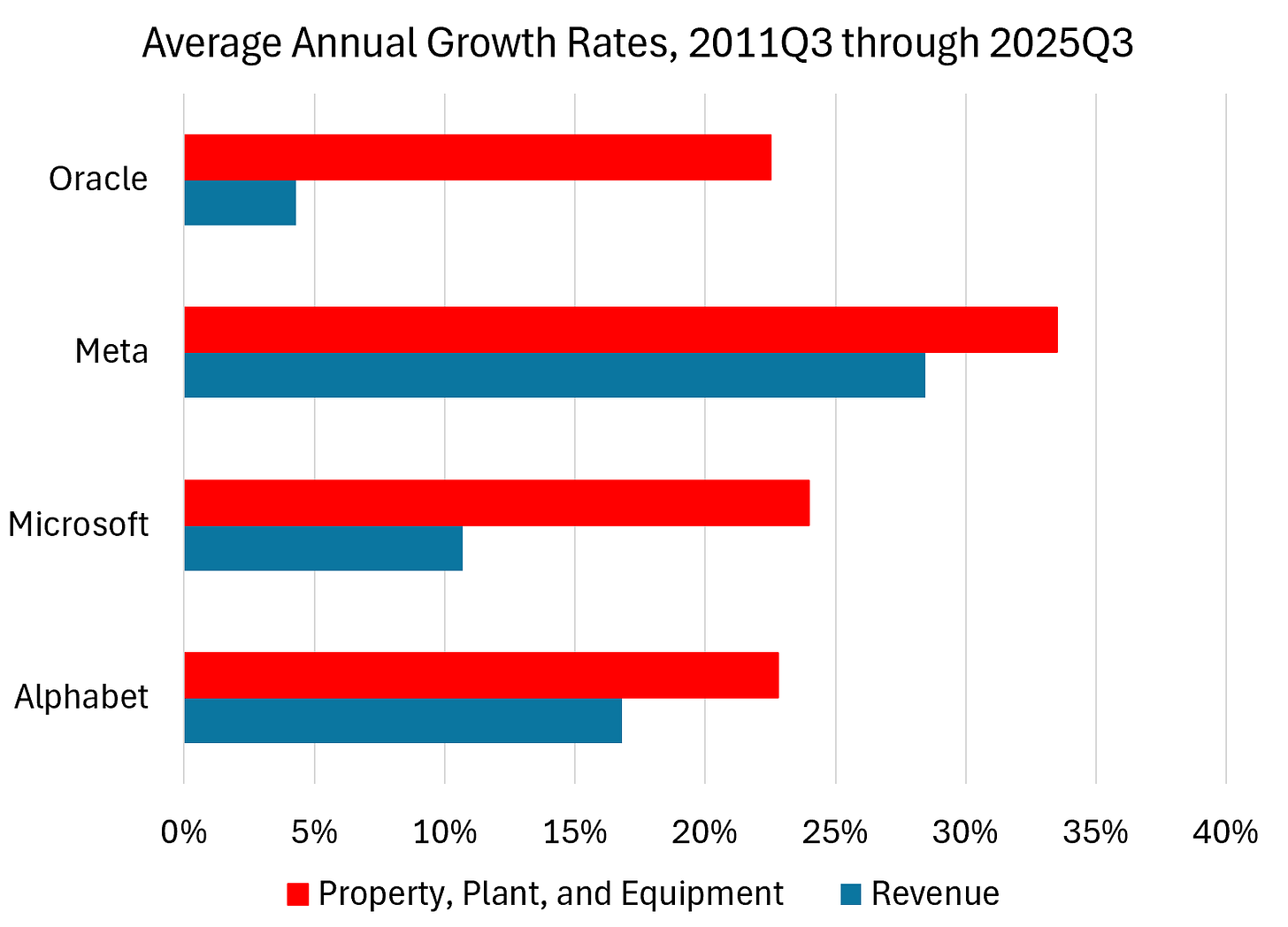

Figure 2 compares the average annual growth rates of PPE and total revenue for Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta, and Oracle between 2011 and 2025.

Growth in Big Tech’s physical capital footprint outstripped revenue growth by a wide margin over the last 15 years.

As a result, these firms are now among the largest owners of productive physical capital in the private sector. Their continued commitments to expand the infrastructure needed to deliver cutting-edge AI models suggest that this trend is unlikely to reverse quickly.

A Balance Sheet Regime Shift

This drastic change in capital allocation is reshaping the balance sheets of Big Tech. Figure 3 shows PPE as a share of total assets for Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta, and Oracle since 2011.

This is the key figure. It shows that not only is investment in PPE rising, but that fixed capital is crowding out other assets that once gave these firms flexibility. Across all four firms, fixed capital now accounts for a much larger fraction of the balance sheet than it did a decade ago.

Assets that once sat largely in cash, marketable securities, and other liquid instruments have been transformed into long-lived, capital-intensive equipment. Intangible capital still matters enormously for these businesses, but relative to fixed capital it now represents a much smaller share of total assets, altering both the risk profile and the durability of returns.

For example, in 2011 PPE on Alphabet’s balance sheet was roughly comparable in size to goodwill and intangibles. As of the most recent quarter, PPE represents nearly six times the value of Alphabet’s goodwill and intangibles.

This represents a fundamental shift in capital allocation.

Importantly, much of this investment has been funded internally. With the exception of Oracle, these firms are not levering up in the traditional sense. Instead, they are redeploying accumulated cash and short-term investments into physical capital. For all but Oracle, the risk is not balance-sheet fragility. It is reduced flexibility in a rapidly changing technological environment.

Cash preserves optionality. Fixed capital does not.

Once deployed, data centers and specialized chips cannot be easily repurposed. Their economic value depends critically on future utilization and the pace of technological change. Consequently, depreciation, both accounting and economic, now plays a much larger role in understanding these firms. In effect, depreciation has become a first-order economic variable rather than an accounting footnote.

Implications for Valuation: FCF Yield

This balance-sheet transition has direct implications for valuation, particularly for metrics based on free cash flow (FCF), which is defined as operating cash flow minus capital expenditures. For asset-light firms, or for asset-heavy firms that are not rapidly expanding, FCF yield (equal to FCF divided by market capitalization) typically provides a clean measure of how much free cash firms are generating for each dollar an investor invests in the firm. But when firms enter a period of heavy capital accumulation, that measure becomes far less informative about valuation.

Capital expenditures rise immediately, while the revenue they generate arrives with a lag. Free cash flow is therefore mechanically compressed in the short run, even if long-run cash-generating capacity is expanding. This tends to drive down FCF yields.

In the case of AI infrastructure, investments are front-loaded, technologically specific, and subject to rapid economic obsolescence. Maintaining capacity is likely to require continuous reinvestment in rapidly depreciating chips rather than one-time spending. If a growing share of revenues are allocated toward maintenance rather than expansion, the implications for long-run free cash flow are very different.

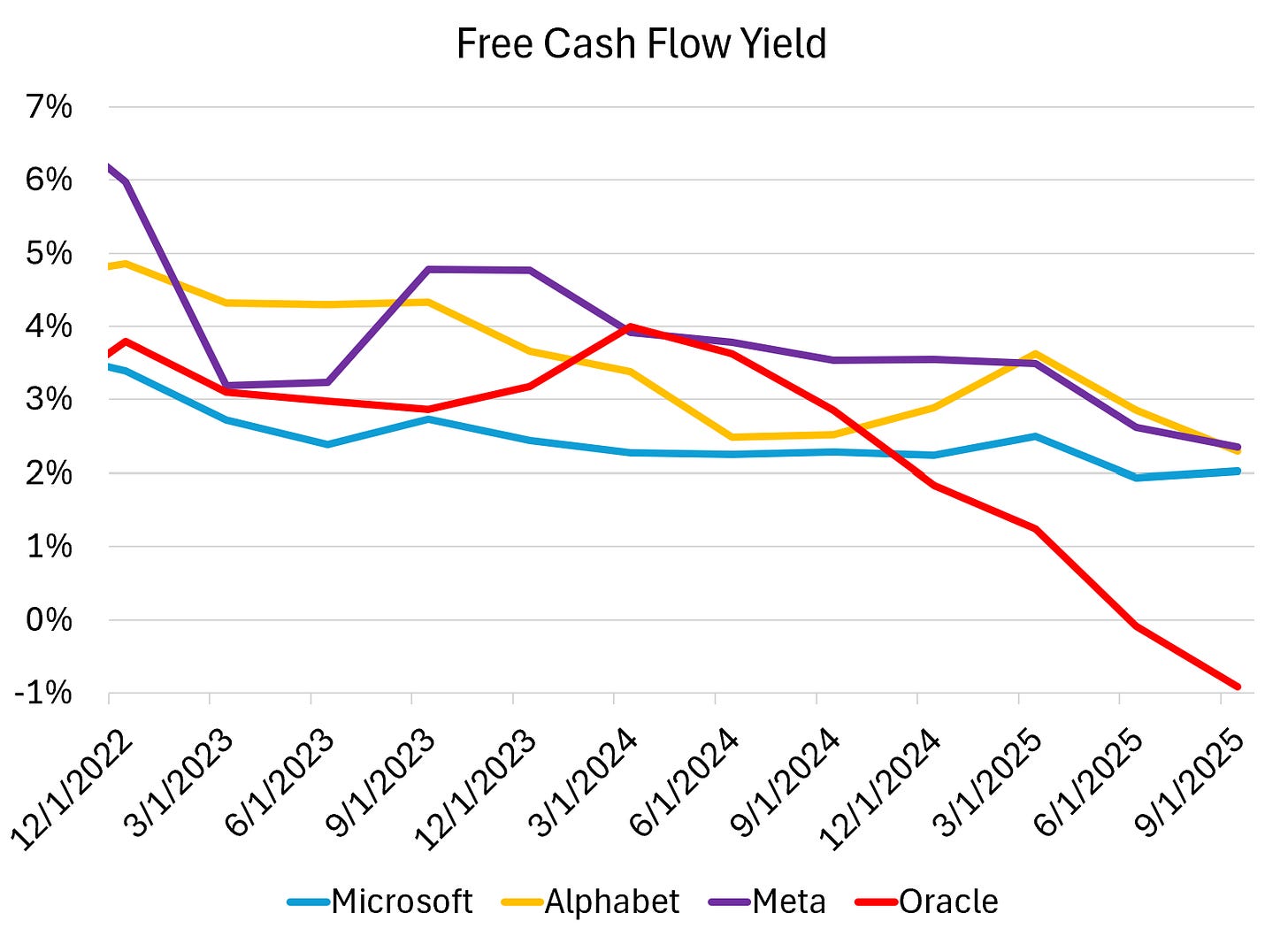

This dynamic is already visible in recent valuation metrics. Figure 4 shows the FCF yields of Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta, and Oracle have declined meaningfully in recent years as their market caps have increased while rising investment in PPE has slowed growth in their FCFs.

At first glance, this looks like a familiar story. Declining FCF yields are often taken as a sign that valuations are becoming stretched. In periods of heavy capital accumulation, however, they can instead reflect the timing mismatch between upfront investment and downstream cash generation.

If markets believe that this spending will eventually generate cash flows that exceed the cost of capital, and the recent rise in market caps suggests that this is indeed the case, equity prices can rise even as free cash flow falls. FCF yields decline not because investors are ignoring cash flows, but because they are looking through a transitory investment phase.

Where the Real Valuation Risk Lies

Taken together, these trends suggest that valuation risk has shifted in an important way. The key question is not whether today’s free cash flow looks expensive relative to market capitalization. It is whether these rapidly growing investments in fixed capital will ultimately earn returns that justify their scale.1

Answering that question requires shifting attention away from short-run cash-flow metrics and toward the economics of returns on incremental capital—an issue that merits separate treatment.

If AI-driven revenues scale smoothly, today’s relatively low FCF yields may prove temporary. As utilization rises and capital spending normalizes, free cash flow could rebound sharply, driving up FCF yields.

If revenues fail to materialize, however, the downside looks different than in the past. Depreciation will continue to rise independent of revenue growth. Maintenance capex will be required even if growth slows, creating a persistent drag on free cash flow. And the cash that once provided a buffer against uncertainty has already been spent.

A Different Kind of Big Tech

A defining feature of the AI era is likely to be the transformation of Big Tech into some of the most capital-intensive firms in the economy.

This is a familiar dynamic in capital-intensive industries. Railroads, utilities, and telecommunications firms have all experienced periods where heavy investment distorted traditional cash-flow-based valuation metrics. What is new is seeing this dynamic play out at firms that investors have long treated as archetypal, asset-light software businesses.

As the figures above clearly demonstrate, this transformation is already well underway. Balance sheets are tilting toward fixed assets. Cash and short-term investments are being converted into long-lived, rapidly depreciating capital. Free cash flow, once remarkably stable, is coming under pressure as investment cycles lengthen and the need for ongoing physical capital investment rises.

In this new regime, falling FCF yields are not, by themselves, evidence of excess or irrational exuberance. They reflect the fact that capital is being deployed today to secure compute capacity that may only be fully monetized years from now.

The real valuation question is no longer simply whether these firms look expensive relative to current free cash flow. It is whether the returns on this expanding base of productive capital will ultimately justify its scale.

Big Tech is no longer just writing code. It is building infrastructure. And that shift changes how we should think about valuing these businesses.

If you enjoyed this mildly efficient and occasionally rational look into Big Tech’s balance sheet regime shift, consider subscribing below. We’ll keep exploring markets and models, uncovering mildly surprising truths along the way.

No hot takes; just thoughtful ones.

About the Author: Seth Neumuller is an Associate Professor of Economics at Wellesley College where he teaches and conducts research in macroeconomics and finance. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from UCLA. His Substack is Mildly Efficient (and Occasionally Rational) where he explores topics in finance and macro from first principles, cutting through complexity with clear, grounded analysis.

Notes and Sources

AI tools were used to edit prose; all figures are straightforward to reproduce from the cited sources.

Greater capital intensity may also raise barriers to entry and entrench incumbents, increasing the dispersion between winners and losers.