Even at $950 per Share, Costco's Stock May Still be a Bargain

Costco’s Stock Sports a PE Ratio Similar to Nvidia, But That Doesn’t Mean It’s Overpriced

Disclaimer: The information in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as financial or investment advice. The views expressed are those of the author and do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any security. Readers should conduct their own research and consult a licensed financial advisor before making any investment decisions. The author does not currently hold shares of Costco Corporation directly but may have indirect exposure through index funds.

TL;DR: Costco’s stock trades at a PE ratio of around 55, which looks absurd at first glance. But dig into the numbers, and that valuation starts to make sense. With near break-even retail margins, Costco effectively monetizes loyalty through high-margin memberships. If it keeps growing free cash flow modestly (say, ~5%), today’s price is justified. And if Costco is able to grow even faster, the valuation math gets a little weird—in a good way.

Intro

Costco’s appeal is legendary. It is a bargain-hunter’s dream and a haven for loyal families and small business owners to stock up on essentials in bulk at discounted prices. Its $1.50 hot dog may be America’s most beloved inflation hedge.

But is Costco’s stock as good a deal as its hot dog combo? At over $950 per share with a price-to-earnings (PE) ratio of around 55, the market is valuing this big-box retailer more like an AI-fueled growth company than a warehouse full of paper towels and Kirkland shirts.

As a (mostly) rational economist and a believer in (mildly) efficient markets, my instinct when I see a valuation this lofty is that either I am missing something, or animal spirits are back at it again.

So I set out to test the market’s logic. And, well… turns out it might be right. Again.

In what follows, we will unpack Costco’s business model and evaluate whether its lofty valuation is justified. Spoiler: I think it is. The key lies in the stability of Costco’s revenue stream and its ability to expand its footprint and sales over time in a cost-efficient manner.

Whether you are a fundamentals-focused investor or just curious why this big-box retailer trades like a tech stock, keep reading to see what the market might be seeing.

Breaking Down Costco’s Business Model

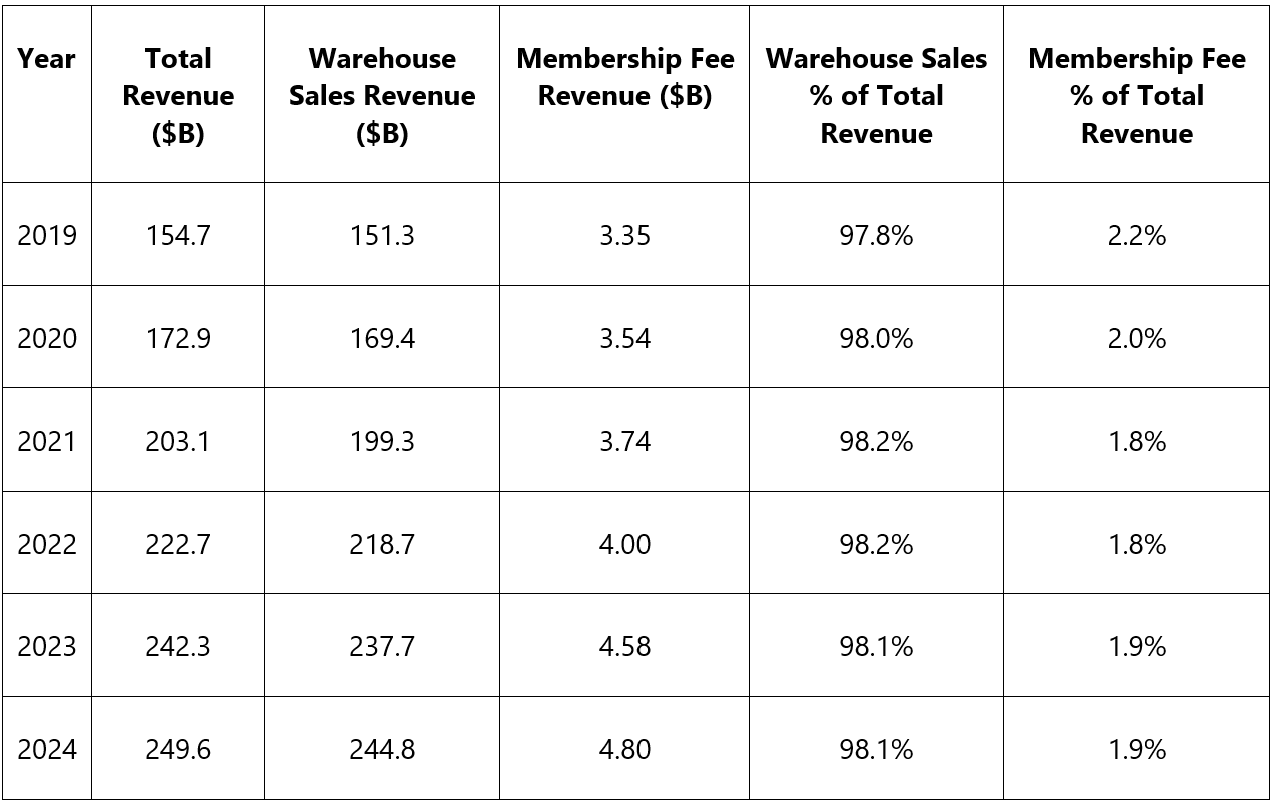

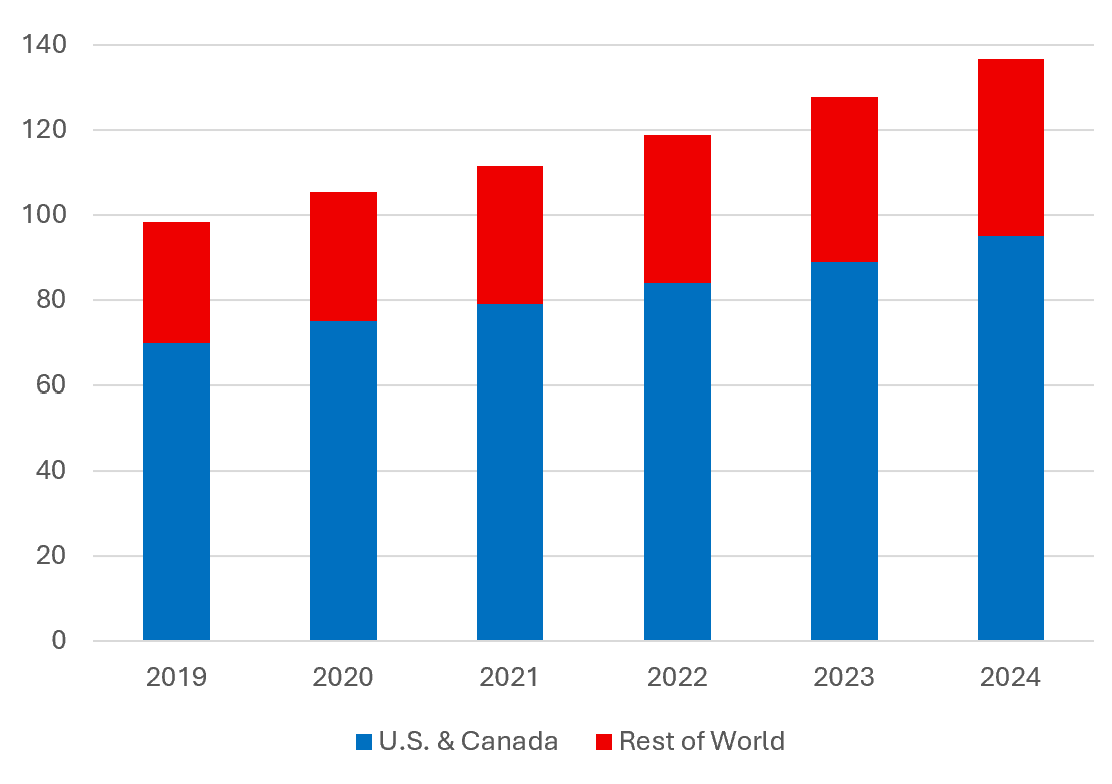

Between 2019 and 2024, both Costco’s warehouse sales and membership fee revenue grew steadily. As Table 1 shows, roughly 98% of revenue comes from merchandise sales, with membership fees contributing just under 2%.

Table 1. Costco’s Total Revenue Breakdown, 2019–2024

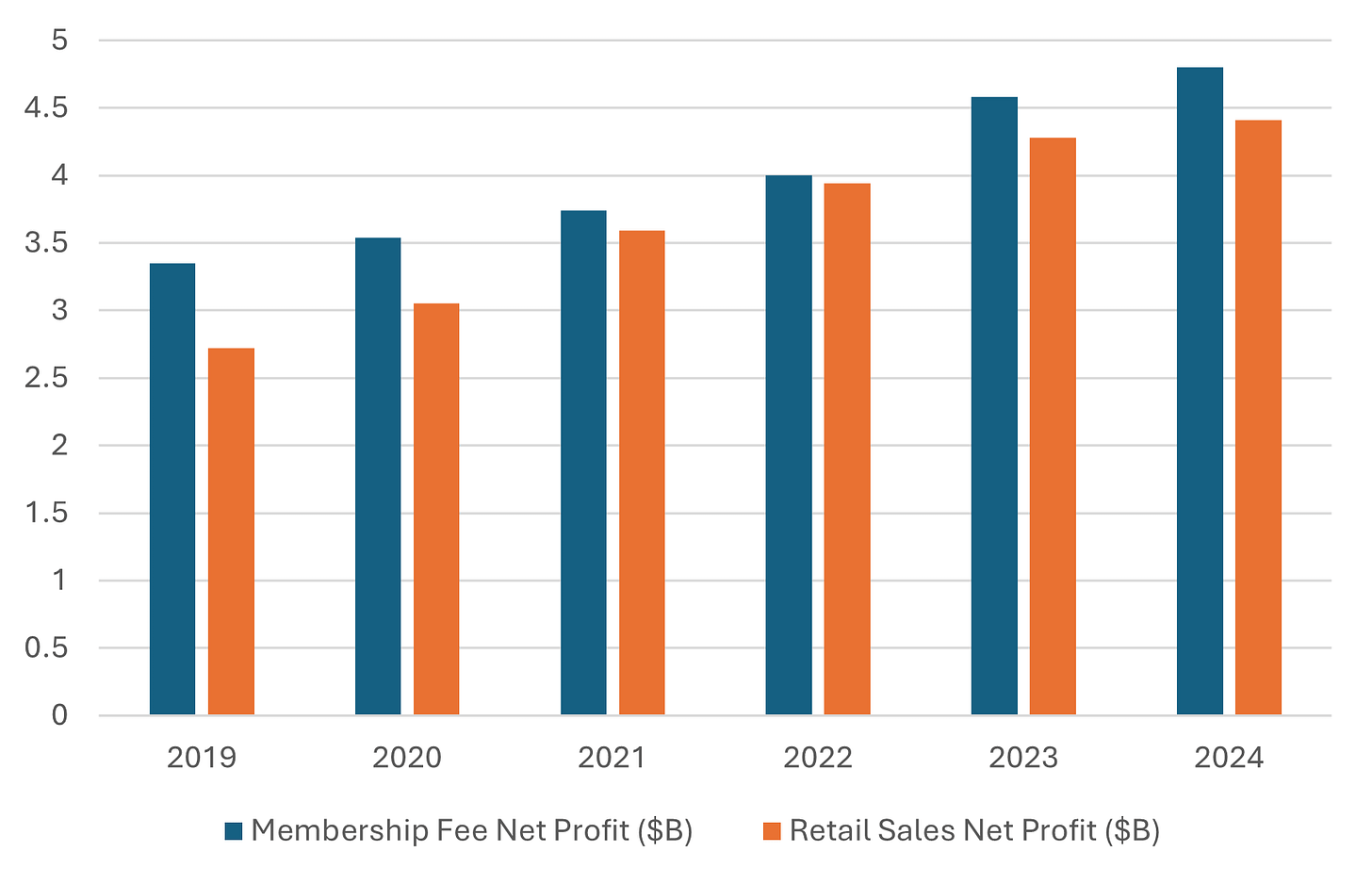

So why focus so heavily on membership fees if they are such a small piece of the revenue pie? Because that is where Costco makes most of its profit.

Costco passes along nearly all of its purchasing savings to customers. Excluding membership fees, its warehouses generate razor-thin operating margins, just 1.5% to 1.8% over the past five years. By contrast, Walmart’s operating margins hovered around 4%.

In essence, Costco operates its retail business at break-even. Members pay prices close to Costco’s actual costs to acquire goods and operate its warehouses. What lifts Costco’s total margins into Walmart territory is the 100% margin membership revenue. In this sense, Costco is less a retailer than a subscription service with a warehouse attached.

Figure 1. Net Profit from Membership Fees vs. Retail Sales, 2019–2024

Translation: the real product Costco sells is not toilet paper or TV sets, it is the membership itself. The warehouse experience is designed to keep customers coming back year after year, paying the fee.

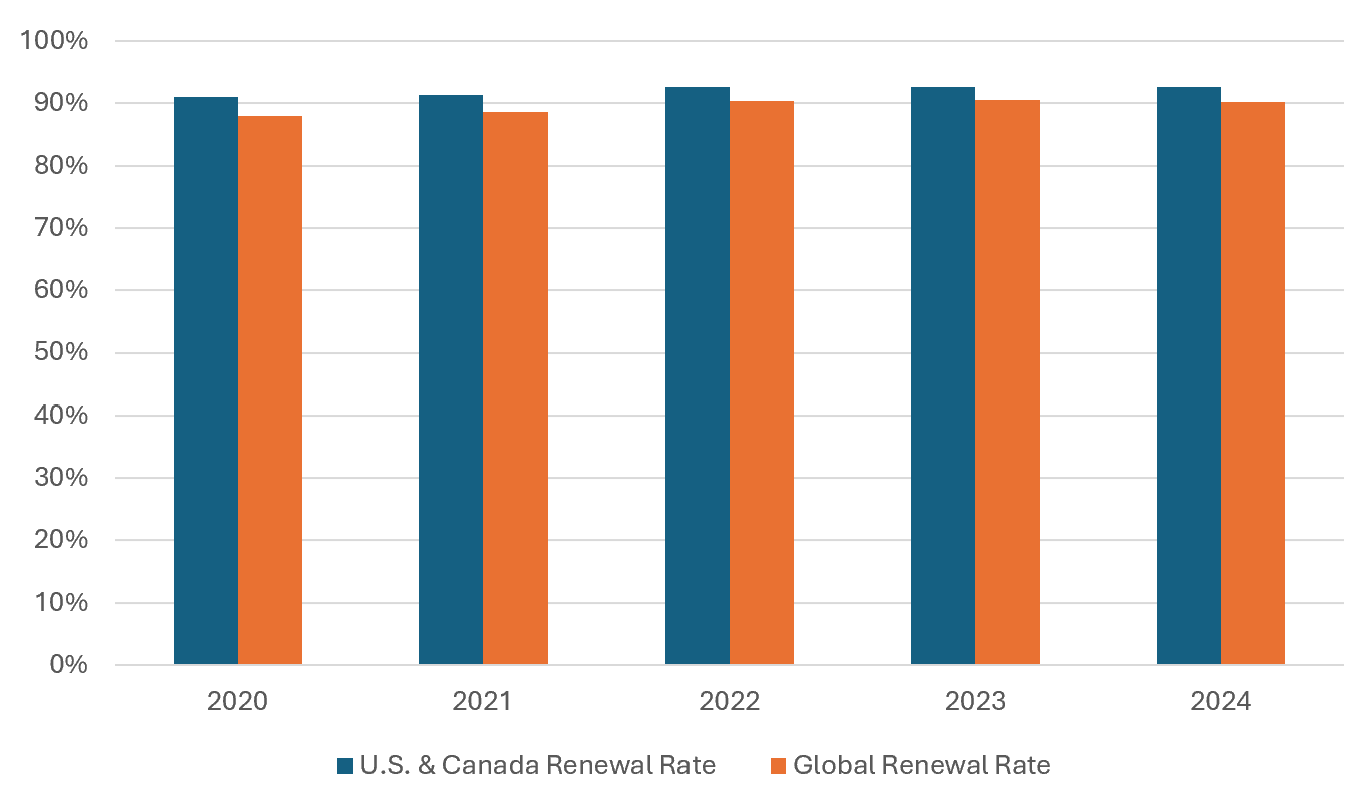

And it is working. Membership renewal rates consistently exceed 90% in the U.S. and Canada. Beyond high renewal rates, Costco has been aggressively expanding into new markets, adding warehouses and growing its global membership base.

Figure 2. Costco Membership Renewal Rates, 2020-2024

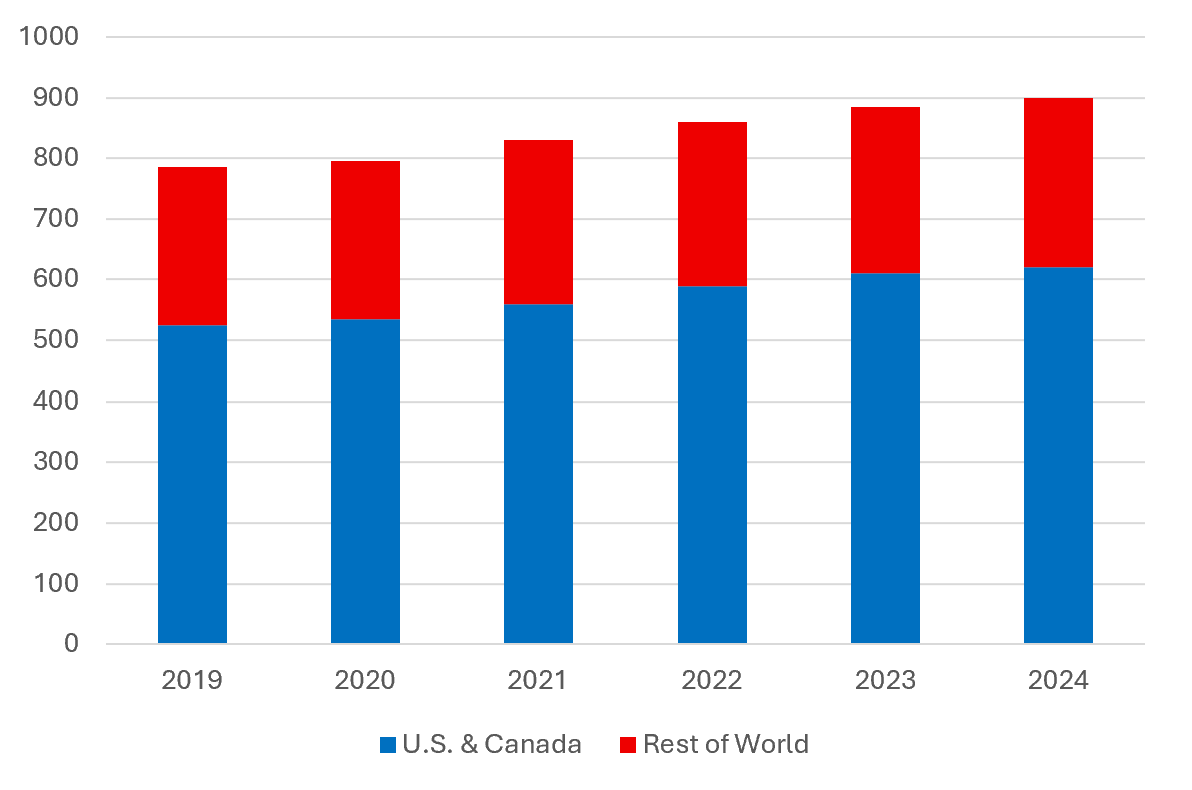

Figure 3. Costco’s Store Count, 2019–2024

Figure 4. Costco Memberships (millions), 2019–2024

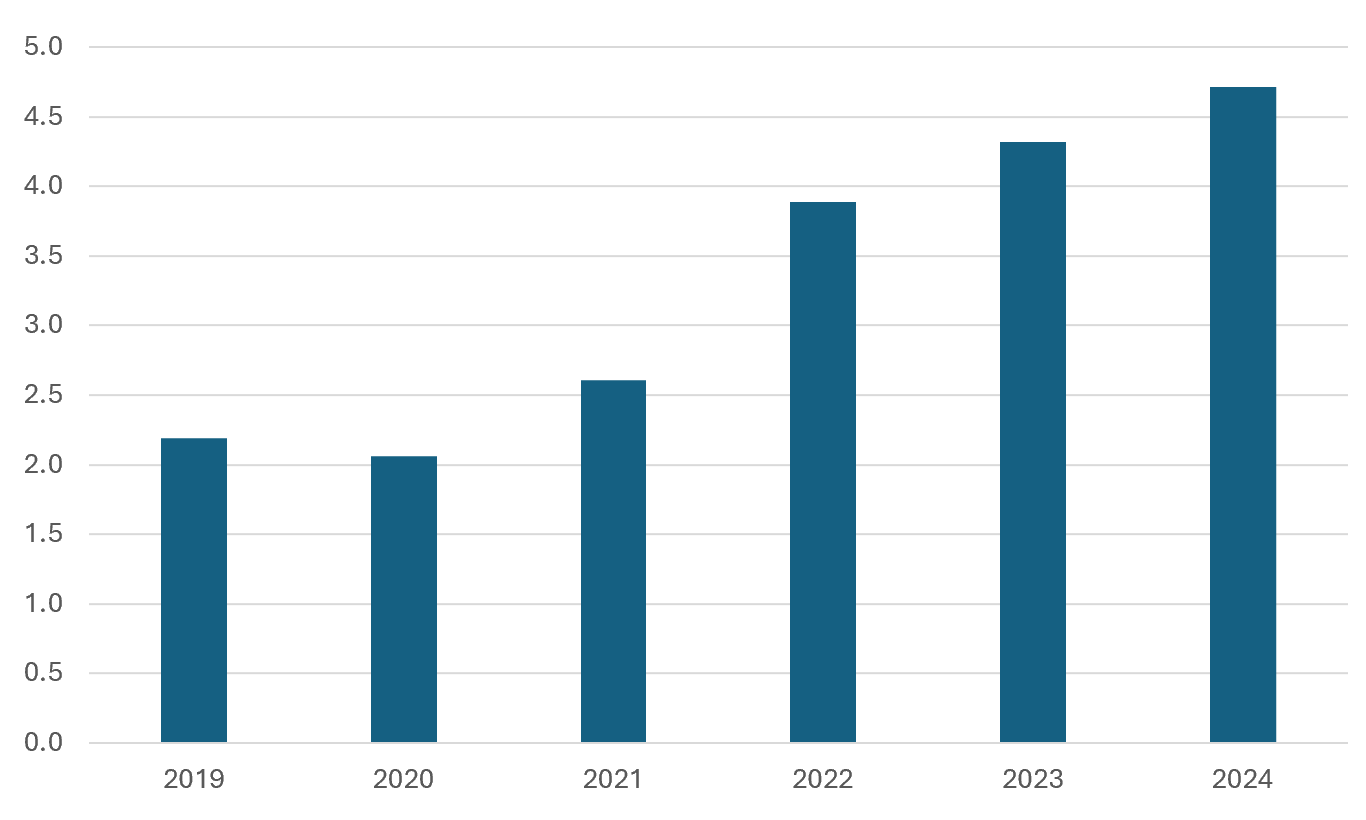

This expansion is not cheap. Capital expenditures more than doubled from 2019 to 2024 to support this growth.1

Figure 5. Capital Expenditures ($ billions), 2019–2024

To sum up: Costco runs low-margin retail warehouses that essentially break even, while generating roughly half its profits from high-margin membership fees. It has grown both revenue streams steadily by expanding its footprint and retaining a loyal customer base.

What the Discounted Cash Flow Math Says (and Doesn’t)

To evaluate whether Costco’s equity is fairly priced, I built a simplified discounted cash flow (DCF) model based on the following assumptions:

Operating margins remain stable

Capital investment grows proportionally with revenue

Membership revenue, retail sales, and capital expenditures all grow at a constant rate (g) in perpetuity

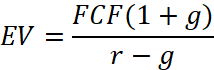

Under these assumptions, free cash flow (FCF) also grows at rate g, allowing us to use the classic perpetual growth model:

where:

EV = Enterprise Value (Market Cap + Debt – Cash)

FCF = Free Cash Flow

g = Perpetual Growth Rate

r = Discount Rate

I assume a discount rate (r) of 7%, consistent with published estimates for large-cap U.S. retailers. Costco’s stable cash flows justify it: half of net income comes from memberships, which are sticky, and a large fraction of retail sales are groceries, which are also stable across the cycle.

As of today:

EV = $422.4 billion

FCF (2024) = $6.6 billion

Solving for the perpetual growth rate implied by Costco’s current valuation, free cash flow, and discount rate yields 5.4%.

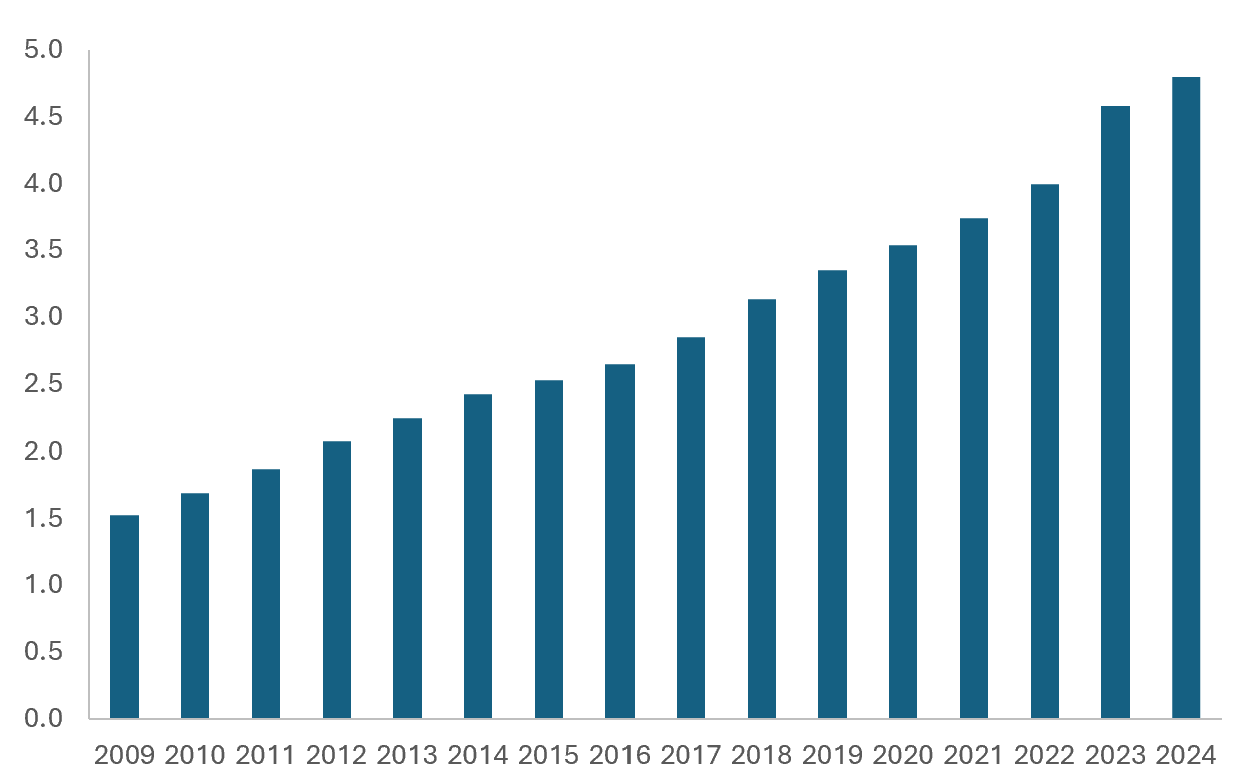

Is that reasonable? I think so. Membership fee revenue has grown at an average annual rate of 6.7% since 2009, with retail sales tracking membership growth. While U.S. warehouse saturation may slow domestic growth, international expansion remains a viable engine.

Figure 6. Membership Fee Revenue ($ billions), 2009–2024

If Costco can continue growing FCF at just 5.4% while keeping capital expenditures in check, the current valuation holds up well.

That Absurd-Looking PE Ratio? Let’s Talk.

If g approaches r, the denominator in the valuation formula shrinks, and the valuation explodes. In Costco’s case, r = 7%, reflecting its remarkably stable, recession-resistant cash flows. That means if Costco even comes close to growing its free cash flow at 7% over the long run, the model says the stock’s fair value heads toward infinity, and the PE ratio does too.

That is not a prediction. It is just math.

Why does the valuation explode as r approaches g? When the growth rate of free cash flows nearly matches the discount rate, future cash flows do not shrink much in present value terms. Each remains almost as valuable as the last in today’s dollars, essentially forever. When you sum them up, you are adding an infinite stream of payments that barely decay. The result is that the present value of free cash flows heads toward infinity.

So… Is Costco Cheap, Expensive, or Just Right?

So yes, despite its PE ratio of around 54, Costco’s stock appears fairly valued. The math checks out: if FCF grows at 5.4%, the stock is priced appropriately. And if growth inches closer to 7%, the implied valuation climbs dramatically.

In short, this humble warehouse retailer with cult-like loyalty and razor-thin retail margins may be one of the most elegantly constructed businesses in America. And maybe, just maybe, its stock price reflects that.

If you enjoyed this mildly efficient and occasionally rational deep dive into Costco’s current valuation, consider subscribing below. We’ll continue exploring markets and models, revealing mildly surprising truths. No hot takes. Just thoughtful ones.

About the Author: Seth Neumuller is Associate Professor of Economics at Wellesley College where he teaches and conducts research in macroeconomics and finance. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from UCLA. His substack is Mildly Efficient (and Occasionally Rational) where he explores topics in finance and macro from first principles—cutting through complexity with clear, grounded analysis.

Not all of Costco’s capital expenditures during this period went toward building new warehouses. A substantial fraction was invested in building out Costco’s online presence, as well as reinvesting in existing warehouses.