What the Data Really Say About the Job Market for New Grads

The latest data show a familiar seasonal pattern, not a white-collar recession

Recent Wall Street Journal coverage paints a grim picture for new graduates, citing mass layoffs at Amazon, Target, and other large employers. A companion piece describes tens of thousands of white-collar workers being laid off as “AI starts to bite,” leaving new college graduates facing a job market that suddenly feels far less inviting.

Many have speculated that the challenging job market for recent graduates reflects some combination of pandemic-era overhiring, the rise of AI reducing demand for entry-level workers, or broader macro uncertainty, such as shifting tariff policy.

There’s no doubt that for those new grads who are still searching for their first job, this period can feel especially discouraging. Starting a career in a cooling labor market is never easy, and the mix of headlines about layoffs and automation only amplifies that anxiety. That’s exactly why it’s worth stepping back and looking at what the numbers actually show.

As I’ll argue below, based on the data available today, the picture for new grads looks far less dire than the headlines suggest.1 The data reveal remarkably consistent patterns, both across the seasons and over the long run.

Specifically, I will examine unemployment rates using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics for 20- to 24-year-olds, the group that captures most new entrants to the labor market with a bachelor’s degree. To separate seasonal noise from real weakness, I’ll mainly be using data that is not seasonally adjusted. As it turns out, this approach yields important insights into the job market for new grads.

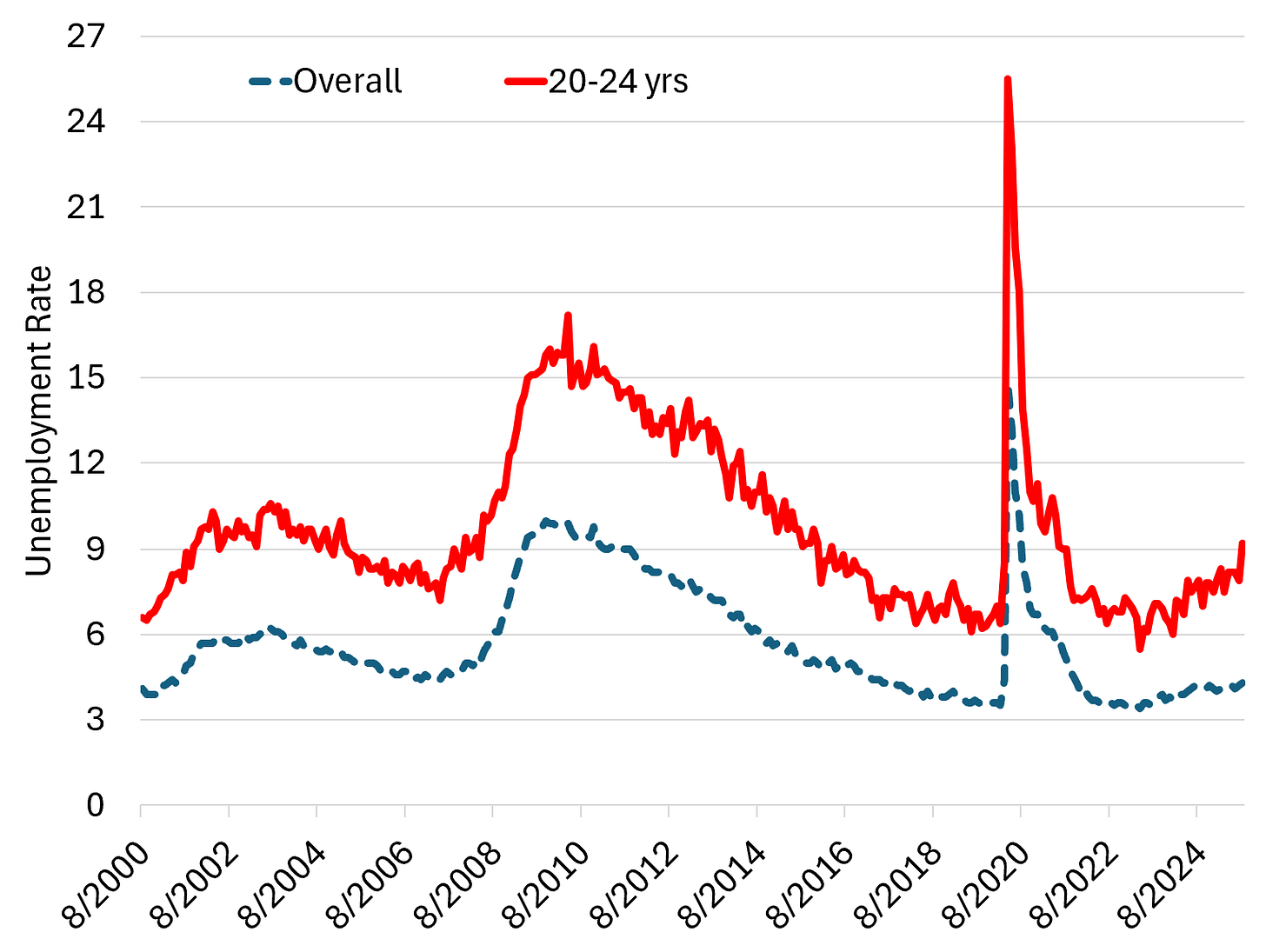

Young Workers Always Have a Higher Unemployment Rate

The first observation is that young workers generally have a higher unemployment rate than the economy-wide average (Figure 1). Indeed, the unemployment rate for 20- to 24-year-olds typically runs between 1.5–2 times the overall unemployment rate, a relationship that has held remarkably steady for decades.

Young workers have had a higher unemployment rate in every cycle, from the dot-com bust to the post-COVID expansion. This reflects normal labor market churn: young people are typically entering the workforce for the first time and switch jobs frequently, both of which tend to raise their unemployment rate relative to older, more established workers.

So while the unemployment rate for 20- to 24-year-olds has ticked up recently, increasing the gap between it and the overall unemployment rate, it’s still well within its normal range.

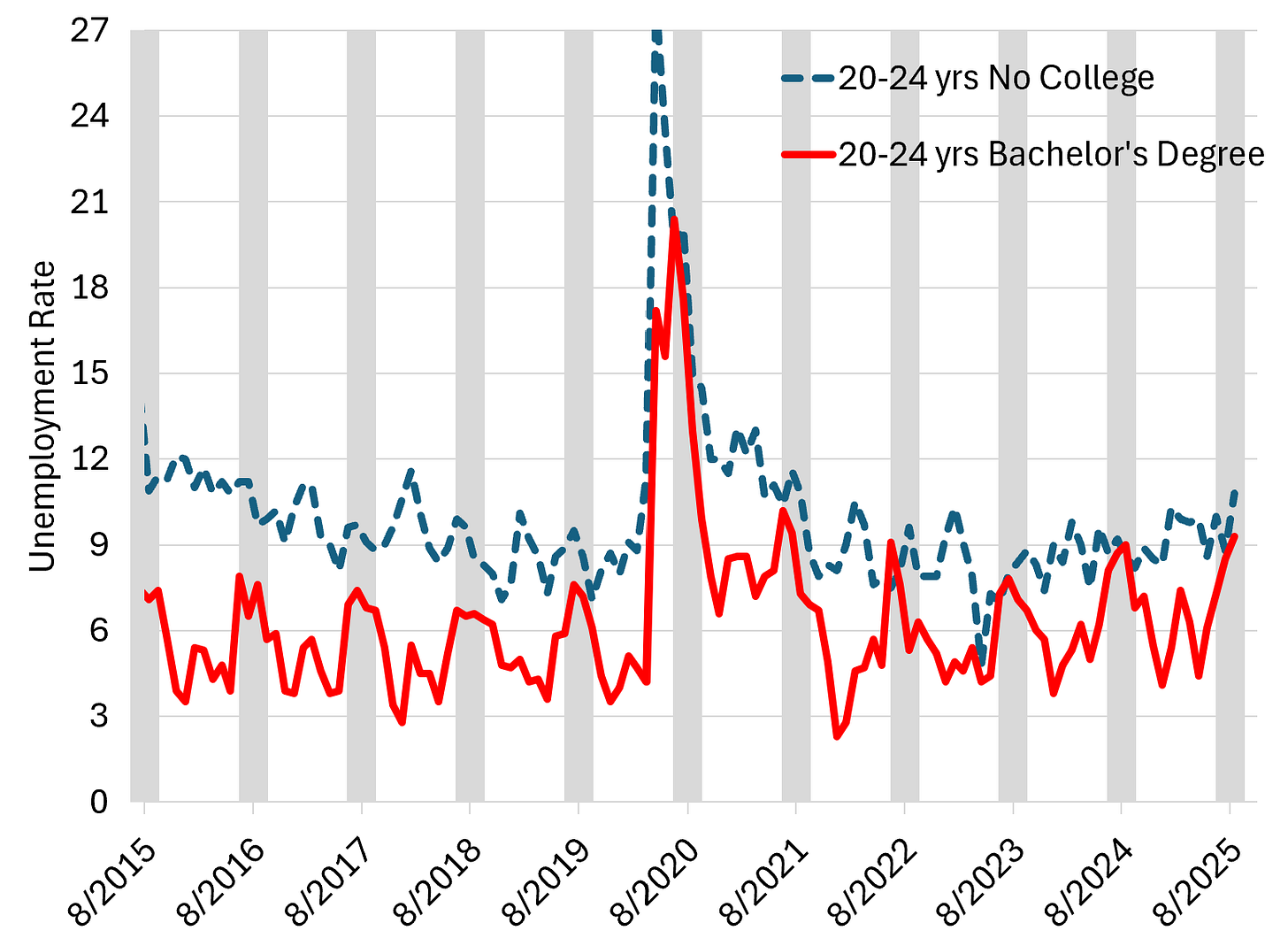

Summer Spikes are Normal and Entirely Predictable

Every summer, the unemployment rate for workers aged 20-24 with a bachelor’s degree jumps sharply (Figure 2). The reason is simple: it is graduation season. Thousands of undergraduate students finish school and enter the labor force during the summer, and it takes time to find their first full-time job.

This seasonal pattern is so strong that the unemployment rate for recent college graduates sometimes rises above that of similarly aged workers without a college education, albeit briefly. This reversal happened during the summers of 2022, 2023, 2024, and it came close to happening again this past summer. But come fall, the unemployment rate for recent college graduates tends to settle back below that of their less educated peers.

It follows that this year’s “spike” in unemployment is not necessarily a warning sign; it’s expected and entirely normal.

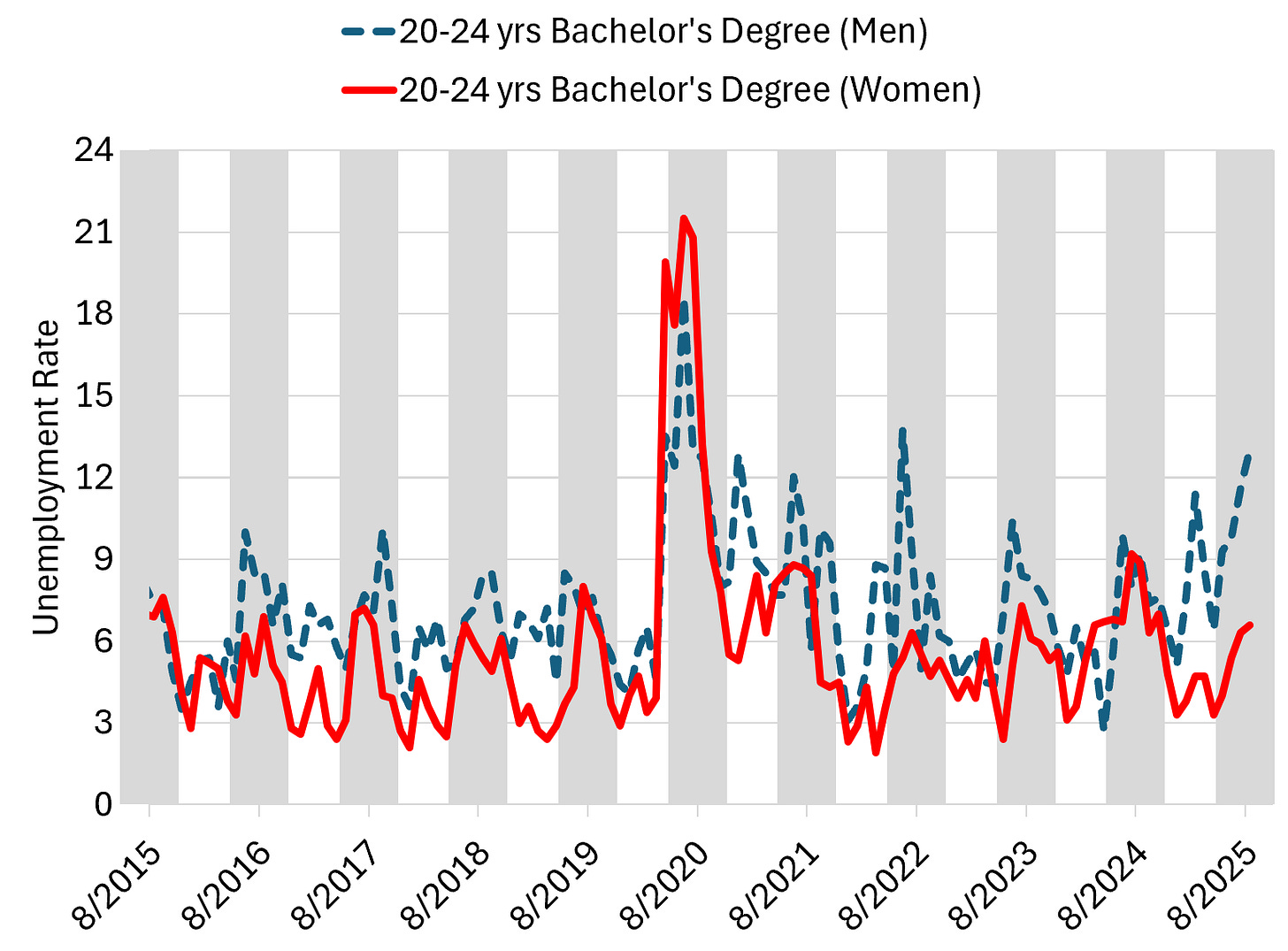

Summer Spikes are Mostly Driven by Men

The unemployment rate for males who recently graduated from college tends to rise more during the summer than for their female peers, a pattern that held true again this past summer (Figure 3). The reasons could range from industry mix to graduate school enrollment or simple timing differences in job search. Whatever the cause, the gender gap reinforces a simple point: while joblessness imposes a real hardship on individuals struggling to find work, as of today the data point to a familiar seasonal pattern, not a white-collar recession.

The Bottom Line

Despite headlines about corporate layoffs and “AI eating white-collar jobs,” there’s little evidence that new graduates face a uniquely hostile job market. The summer uptick in unemployment of recent grads happens every year, and by fall, most find work. Still, for those searching, the wait can be excruciating, especially when every news alert seems to confirm their worst fears. The transition from college to career nearly always takes patience, and perhaps this year, a bit more of it.

Of course, none of this means AI and automation won’t reshape the white-collar job market eventually. But for now, the data tell a simpler story. The rhythms of graduation season and the temporary spike in unemployment that comes with it are as steady as ever.

For now, the Class of 2025 can take comfort in knowing that what they’re experiencing is both temporary and entirely normal.

If you enjoyed this mildly efficient and occasionally rational take on the job market for recent college grads, consider subscribing below. We’ll continue exploring markets and models, revealing mildly surprising truths.

No hot takes; just thoughtful ones.

About the Author: Seth Neumuller is an Associate Professor of Economics at Wellesley College where he teaches and conducts research in macroeconomics and finance. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from UCLA. His Substack is Mildly Efficient (and Occasionally Rational) where he explores topics in finance and macro from first principles, cutting through complexity with clear, grounded analysis.

Notes and Sources

AI tools were used to edit prose; all figures are straightforward to reproduce from the cited sources.

The data referenced in this post are the most current available, which are through the month of August 2025. Because the Bureau of Labor Statistics has not yet released updated data due to the ongoing government shutdown, my conclusions may change once new numbers are published.