Where Did Labor’s Share of Income Go?

Labor’s share is shrinking, but not because profits are rising.

In intermediate macroeconomics, we often teach that labor’s share of income is roughly constant at about two-thirds, with the remaining third going to the owners of capital. This regularity makes production theory feel intuitive and allows us to represent the U.S. economy with a Cobb–Douglas production function, an elegant and accessible framework for undergraduate students.1

But the data tell a different story.

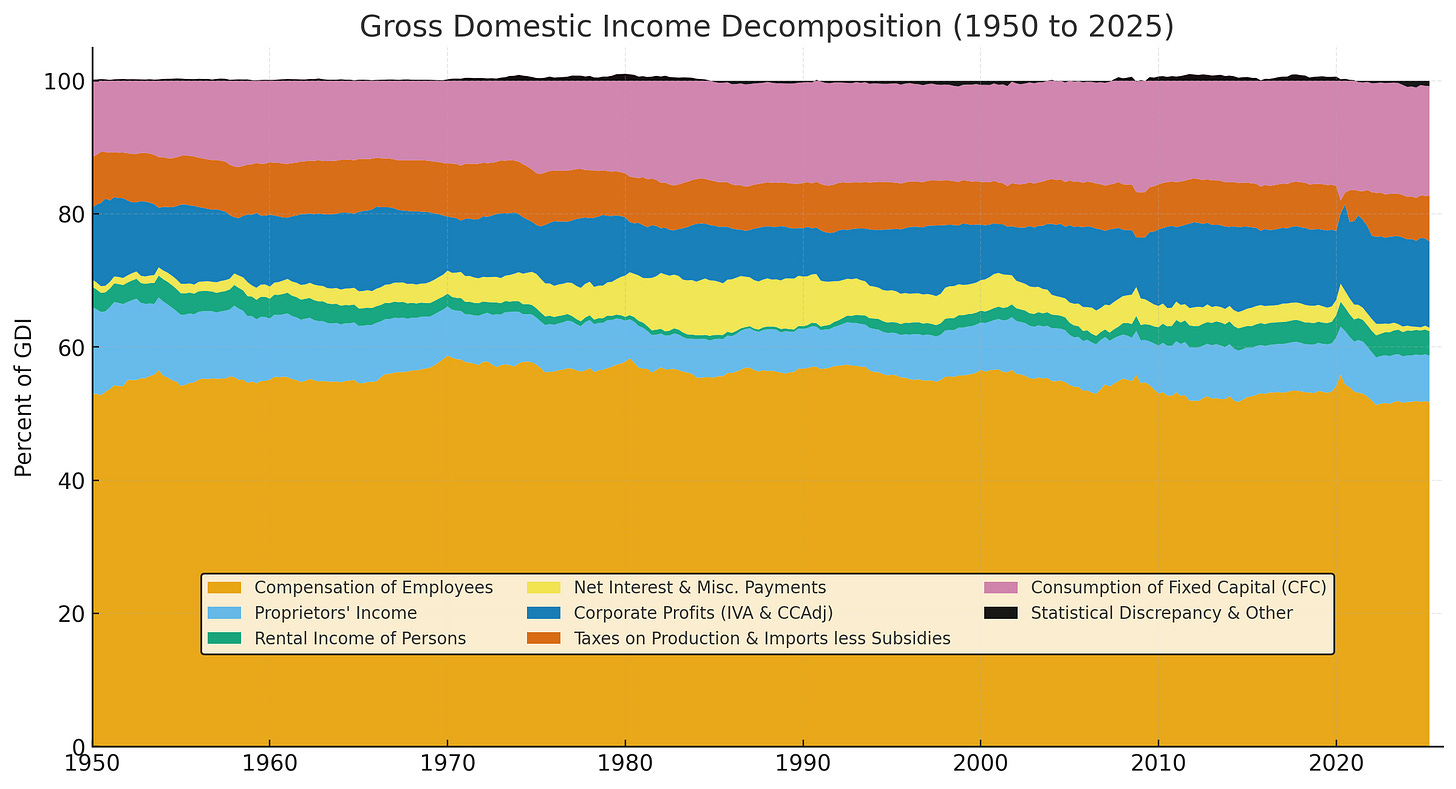

Since 1950, labor’s share of Gross Domestic Income (GDI) has declined steadily, falling from about 66 percent to 58 percent today, a drop of 8 percentage points.

This decline helps explain a familiar sentiment on Main Street: the economy keeps growing, but the typical worker isn’t feeling much better off.

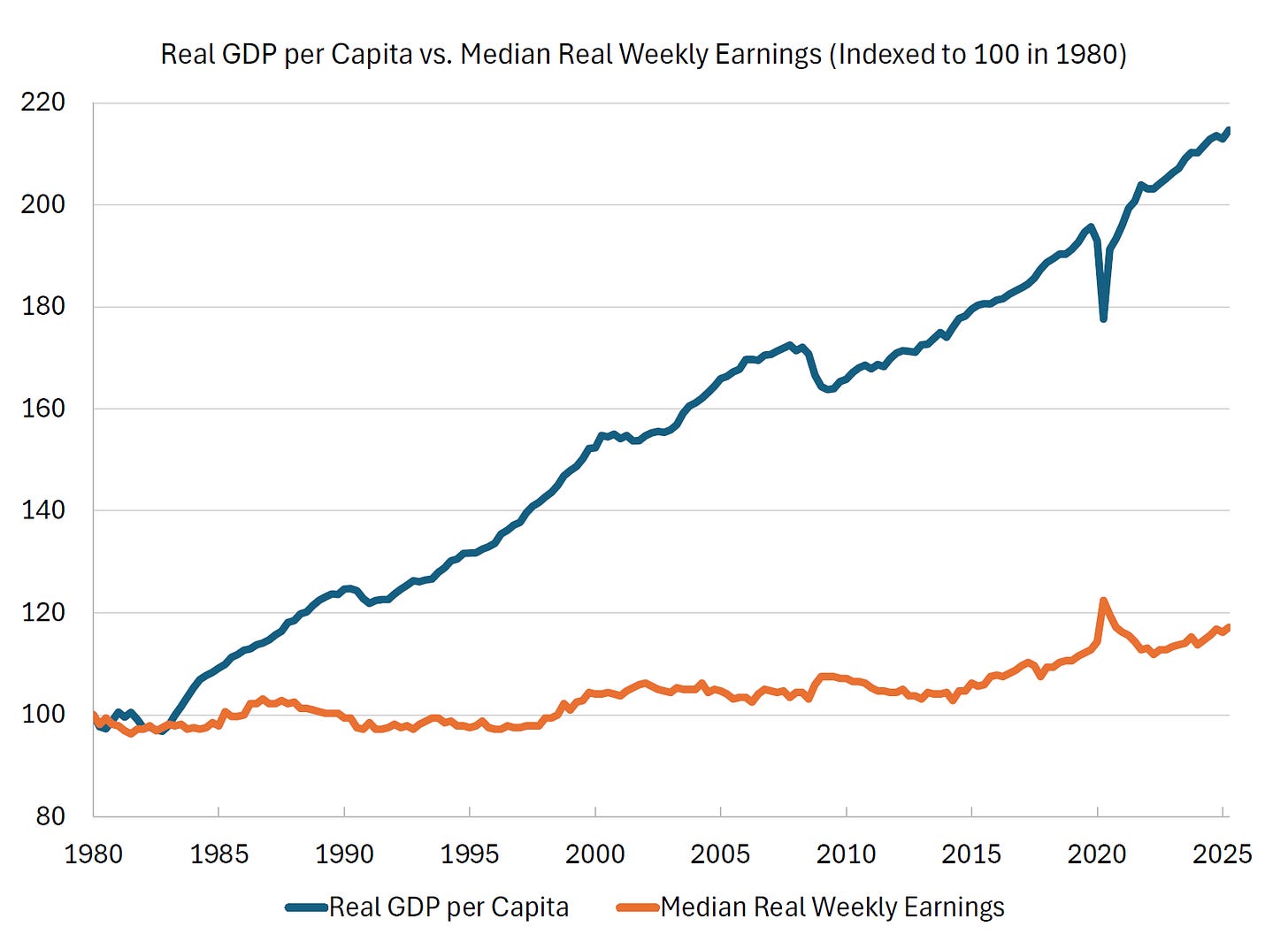

There is perhaps no clearer way to see this divergence than to compare growth in real GDP per capita with growth in real labor income. Between 1980 and 2025, real GDP per capita more than doubled, while median real weekly earnings for workers aged 16 and over barely increased. This growing gap between output and earnings mirrors the long-run decline in labor’s share.

If output is rising yet workers’ share of the pie is shrinking, it is easy to conclude that corporate profits must be growing at labor’s expense.

It’s an intuitive narrative, but it is not quite right.

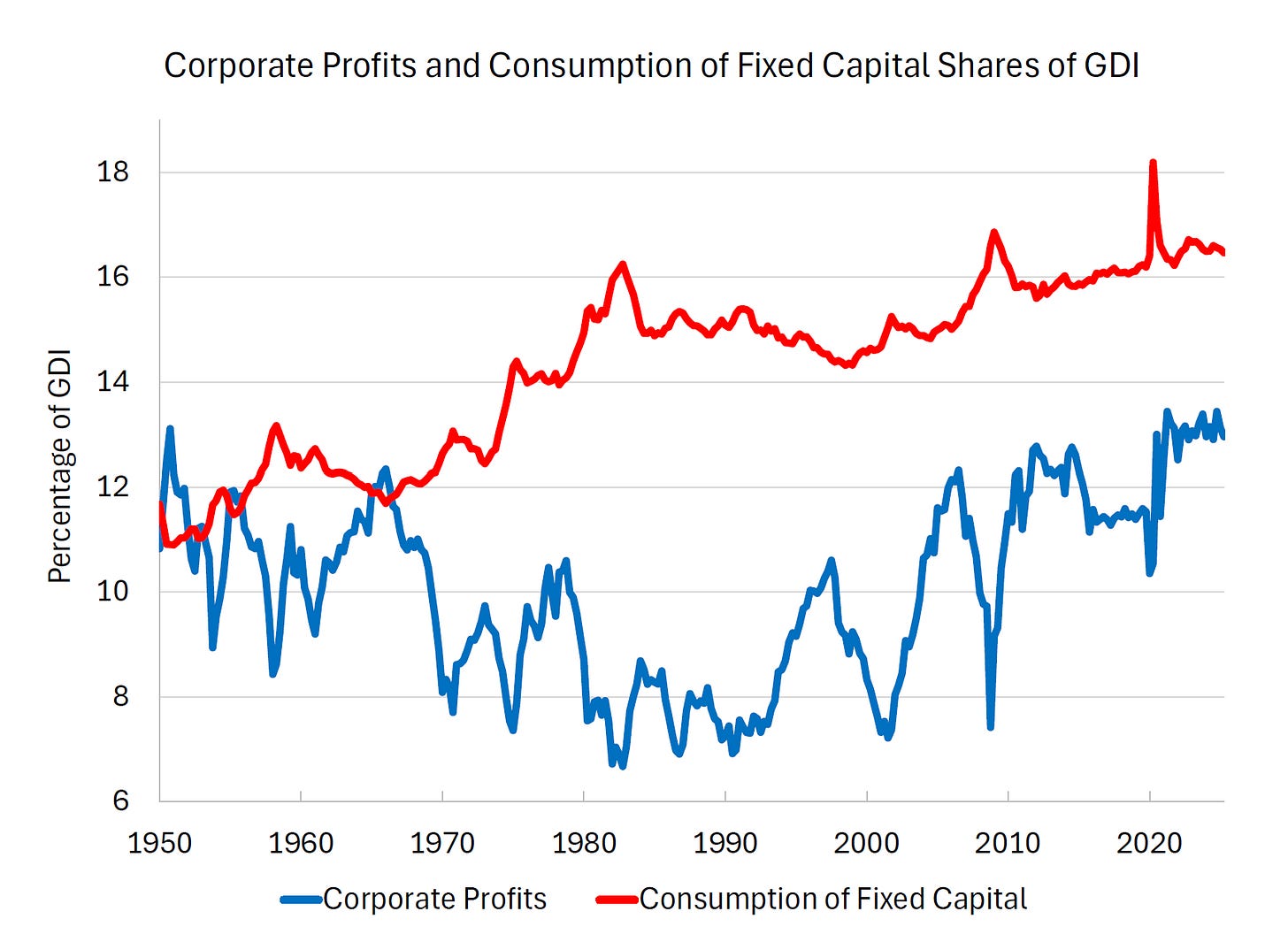

When we break GDI into its components—labor compensation, proprietors’ income, corporate profits, interest, taxes, and consumption of fixed capital—we find that corporate profits have indeed risen, but only modestly. Their share of total income has increased from about 10 percent in the 1950s to roughly 13 percent today, capturing just 3 of the 8 percentage points lost by labor.2

So where did the rest of labor’s share of income go?

The answer lies in consumption of fixed capital, what economists call depreciation. Depreciation’s share of GDI climbed from roughly 11 percent in the 1950s to about 16 percent today, accounting for the remaining 5 percentage points of labor’s loss.

Importantly, depreciation is not income to capital holders. It’s an expense that represents the implicit investment needed to replace or repair broken, worn-out, or obsolete capital.

Rising depreciation reflects an economy whose capital stock is both larger and wears out faster than before. This is especially true in an era of high-tech investment, from servers and GPUs to data centers that become obsolete in years rather than decades. The rise of intellectual property capital—software, databases, and research and development—reinforces this trend. These high-tech and intangible assets depreciate far faster than traditional structures or machinery, so a growing share of income now goes toward maintaining and replacing capital rather than enriching capital owners or lifting real wages.

This observation changes the narrative. Capital owners are not capturing all of labor’s lost share. This nuance matters. It suggests that the tension between Wall Street and Main Street is not simply about profits versus wages. It is about how production has shifted toward capital that is shorter lived and, therefore, depreciates more quickly.

If labor’s share were constant, workers would benefit proportionally from growth. But today, more of what we produce each year goes toward repairing or replacing yesterday’s capital rather than lifting real wages.

A large body of research has sought to explain why labor’s share of income has fallen since the 1950’s. Two of the most influential explanations come from Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century and Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman’s The Global Decline of the Labor Share (2014).

Piketty argues that the share of income accruing to capital rises when its return exceeds the rate of economic growth. In that environment, wealth accumulates faster than output and income naturally shifts toward capital owners. Karabarbounis and Neiman take a different approach. They show that the relative price of investment goods has fallen dramatically since the 1980’s, making capital cheaper and encouraging firms to substitute capital for labor. If capital and labor are easily substituted, this shift can lower labor’s share even as productivity rises.

Both explanations fit the broad narrative that technology and capital deepening have tilted the balance of income away from workers. But they treat capital’s share as a single block that moves in opposition to labor’s. The decomposition here adds an important piece of the puzzle. When we examine GDI in detail, we find that most of the decline in labor’s share reflects the growing cost of maintaining the capital stock rather than an increase in income flowing to owners of capital.

Much of what looks like redistribution from labor to capital may instead reflect a structural shift in the nature of capital itself. Modern production relies on assets that are more technologically sophisticated but also shorter-lived. Servers, GPUs, and intellectual property wear out or become obsolete in just a few years. Their rapid depreciation shows up as a rising expense share in the national accounts, reducing the income available to raise wages or increase returns to capital owners.

In this sense, what looks like redistribution is really a story about the changing composition of productive assets and the costs of sustaining a more technologically advanced economy. It helps explain why the economy can expand while much of the population feels left behind.

In the end, the mystery of the missing labor share is less about rising profits and more about the hidden cost of keeping our ever-expanding, high-tech economy running.

Notes and Sources

AI tools were used to help transform raw data into figures and to edit prose; all calculations are straightforward to reproduce from the cited sources.

If you enjoyed this mildly efficient and occasionally rational take on the falling labor share of income, consider subscribing below. We’ll continue exploring markets and models, revealing mildly surprising truths.

No hot takes; just thoughtful ones.

About the Author: Seth Neumuller is an Associate Professor of Economics at Wellesley College where he teaches and conducts research in macroeconomics and finance. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from UCLA. His Substack is Mildly Efficient (and Occasionally Rational) where he explores topics in finance and macro from first principles, cutting through complexity with clear, grounded analysis.

“Constant labor share” is one of Nicholas Kaldor’s famous “stylized facts” of economic growth, first articulated in his 1957 paper A Model of Economic Growth.

Labor’s share is the sum of labor compensation and proprietors’ income, divided by GDI.