Why the U.S. Labor Market Is Much Harder to Break Than Investors Think

The shift from goods to services has raised the recession threshold

Investors seem to wait on bated breath for every monthly payroll report, scanning it for any hint that the labor market might be rolling over. Each release sends markets swinging between euphoria and anxiety, as traders try to infer the economy’s trajectory from a single noisy data point.

Investors’ intense focus on small month-to-month employment changes is misplaced. The monthly payroll report has a large sampling error, and more importantly, the structure of the U.S. labor market has changed.1 It now takes a much larger shock to push employment into recession than it once did. In practice, this means the next downturn is far less likely to emerge gradually through softening payroll data and far more likely to arrive suddenly, driven by a large, unmistakable shock.

The key reason is structural. As the U.S. economy shifted from goods-producing industries to service-providing ones, total employment became less sensitive to the kinds of disturbances that used to trigger recessions. In short, the structure of employment changed in ways that make typical business cycle downturns less likely, making month-to-month payroll variations less informative than they once were.

In what follows, I walk through how the labor market has changed and why this shift makes the economy far more resilient to shocks that, in the past, would have derailed both employment and financial markets.

For investors, the implication is straightforward: obsessing over monthly payroll numbers is a recipe for misreading recession risk in an economy that now only breaks when it is hit by a truly large adverse shock.

From Frequent Recessions to Rare Ones

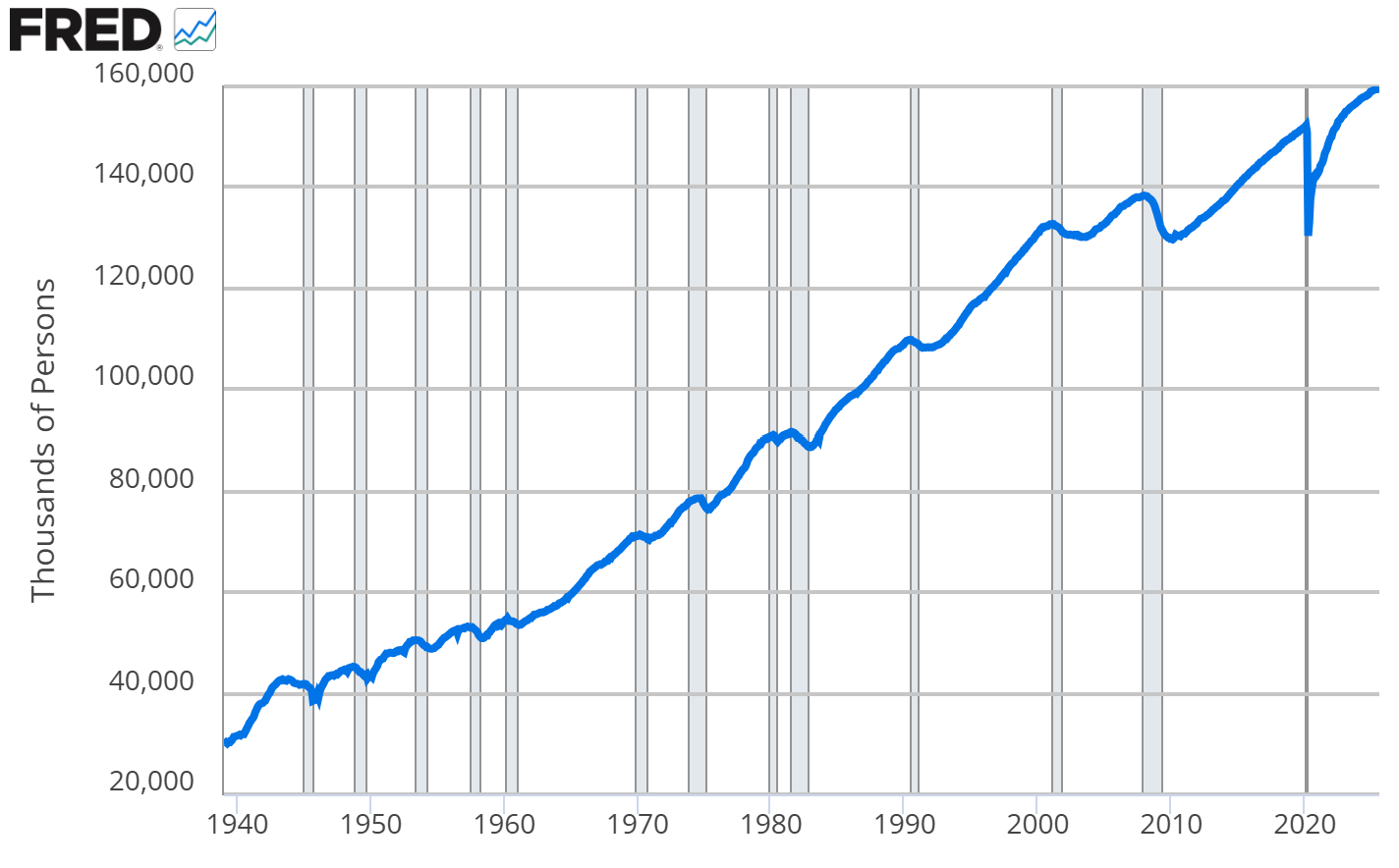

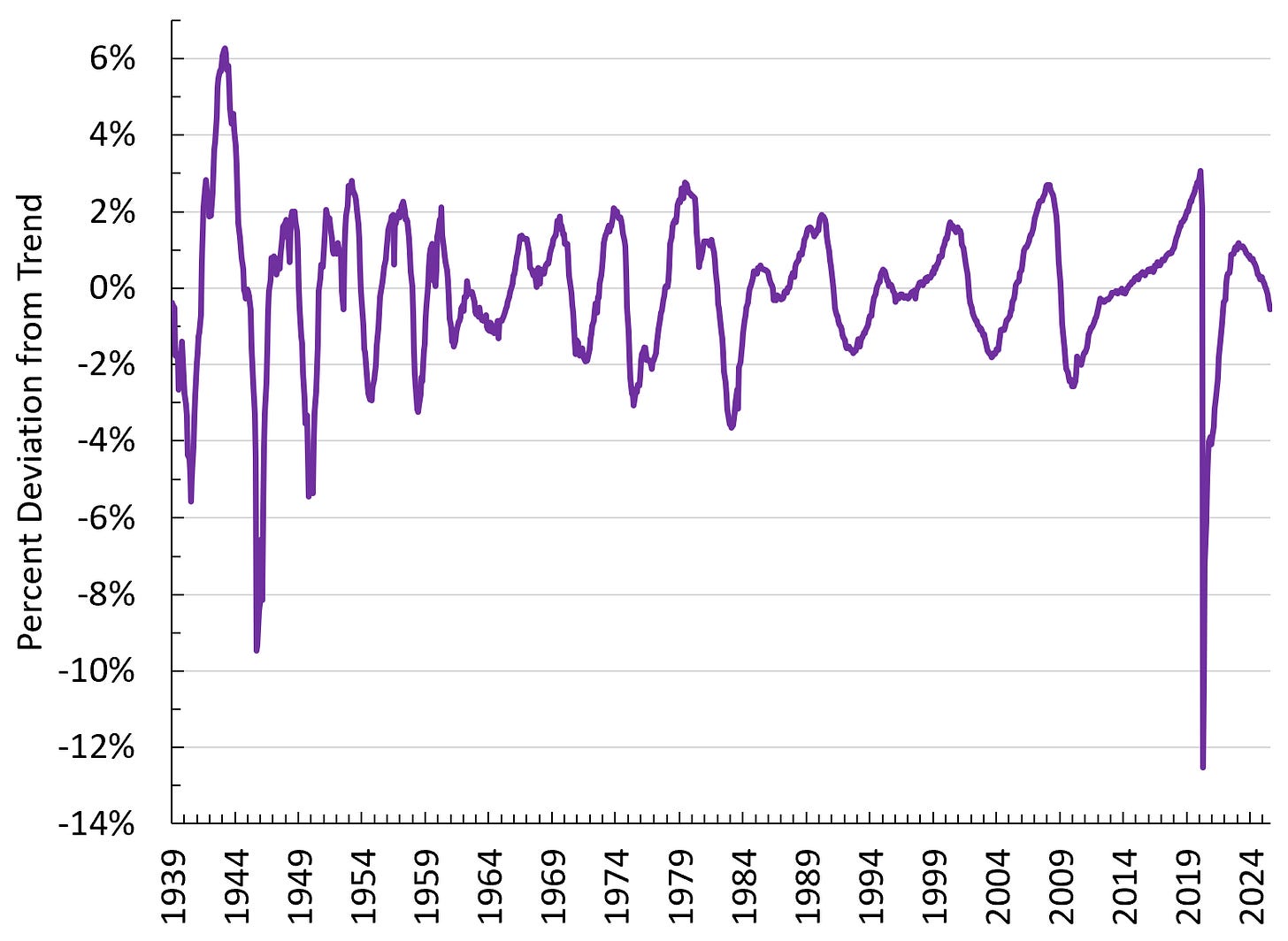

Every recession since the late 1930s has been accompanied by a decline in total employment (Figure 1). This is why investors are right to be laser-focused on the labor market.

But as Figure 1 also shows, recessions have become less frequent over time. The mid-1940s through early 1980s saw downturns every few years, often triggered by war, oil shocks, or monetary tightening. Since the mid‑1980s, the U.S. has endured only four recessions, roughly one per decade.2 Two resulted from extraordinary shocks, namely the global financial crisis and the pandemic‑induced shutdown, and one from the bursting of the dot-com bubble. Moreover, the 1990 and 2001 recessions, while damaging to equity markets, produced only mild and relatively short‑lived declines in total employment.

One interpretation of the fact that recessions have become less frequent is that policymakers became better at managing the economy or more willing to aggressively ease monetary policy and provide fiscal stimulus at the first sign of weakness.

Another explanation, and the focus of this piece, is that the economy itself changed in ways that dampen the economy’s response to a typical recessionary shock. A prime example of this is how the economy withstood the most recent bout of monetary tightening following the high inflation of 2021-22. Nearly everyone, including myself, thought the Fed’s actions would tip the economy into recession. Yet the labor market never rolled over. Instead it remains remarkably resilient.

Does Service or Goods Employment Drive Recessions?

To understand why the economy held up so well despite aggressive tightening, and why it has become more resilient to shocks more generally, it helps to look directly at how different parts of the labor market respond in recessions.

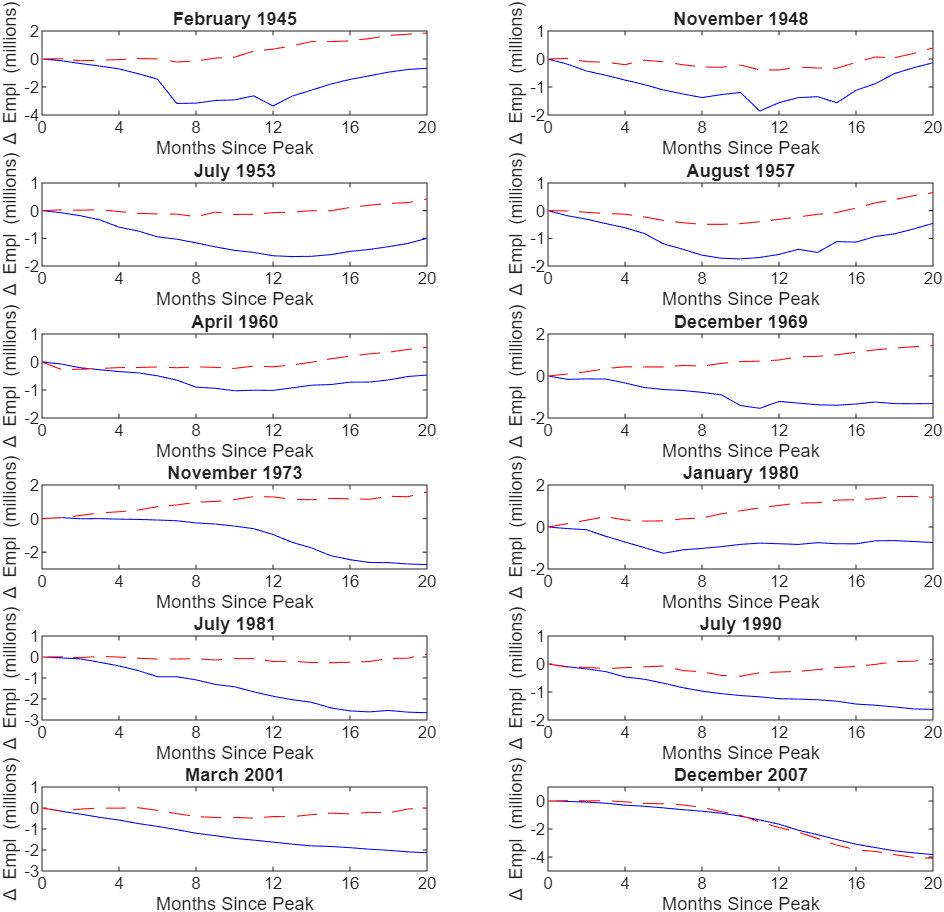

Figure 2 shows that in every recession prior to 2008, goods-sector employment (solid blue lines) fell sharply, while service-sector employment (dashed red lines) barely moved, and in many cases continued rising.

The financial crisis and pandemic recessions were different: both directly hit large service industries (finance/real estate in 2008–09, leisure and hospitality in 2020). Outside these two episodes, service employment has generally held up well during recessions.

A Tale of Two Sectors

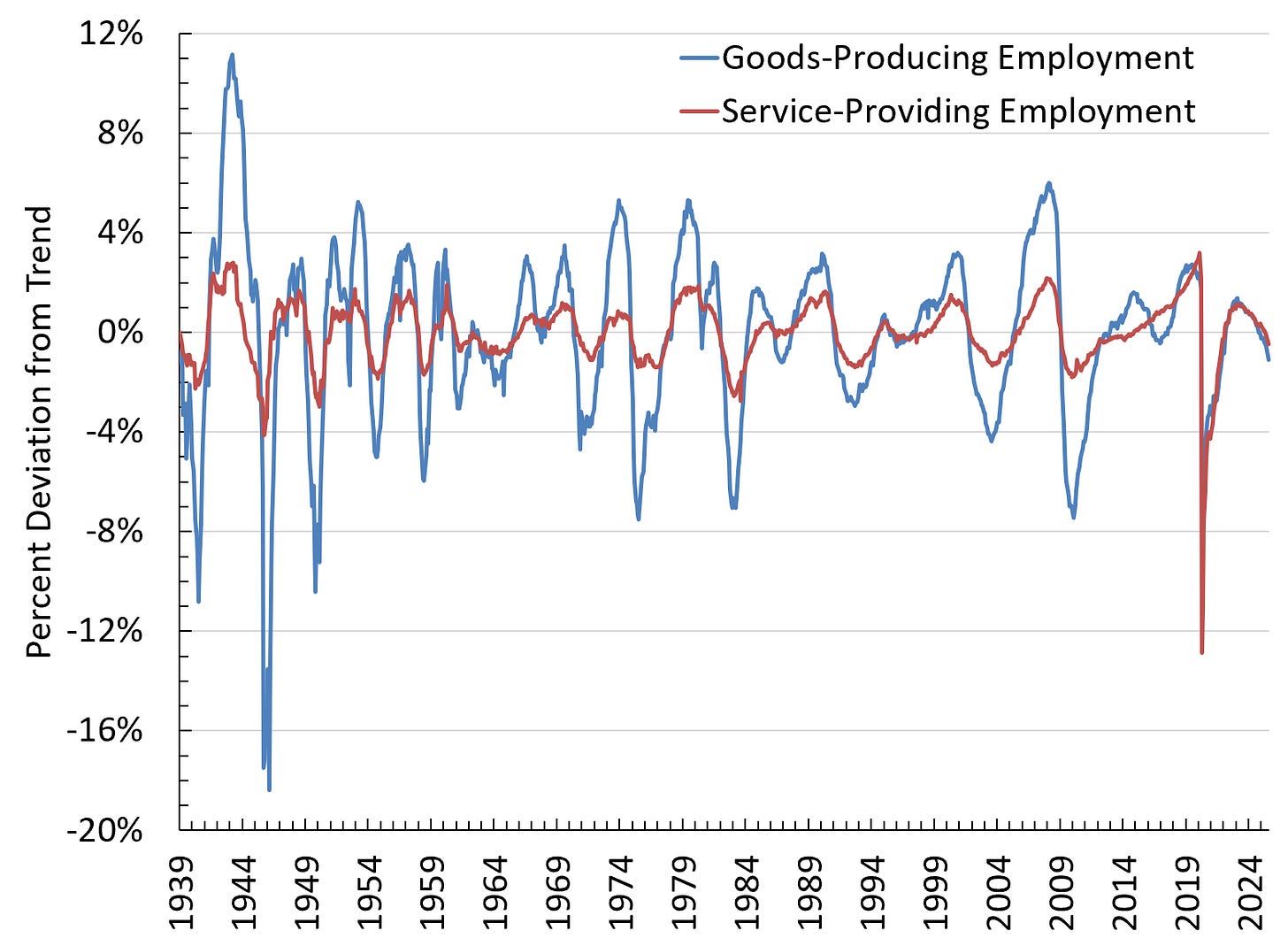

The easiest way to visualize differences across sectors in the sensitivity of employment to economic shocks is to detrend the data and focus in on their business cycle fluctuations. Figure 3 does precisely this by plotting the percent deviation from trend for goods-producing and service-providing employment between 1939 and today.

From Figure 3, we see that goods-producing employment tends to rise quickly during expansions and fall sharply during downturns. Service-providing employment, on the other hand, tends to move in a similar fashion, but more smoothly and with a notably smaller amplitude. The exception, of course, is the COVID recession in which leisure and hospitality employment fell precipitously, pushing service-producing employment well below trend.

Why Are Services More Resilient?

Service-providing employment is inherently more stable for several reasons:

1. Demand doesn’t fall as sharply during downturns. Demand for services like health care, education, and government tends to be highly inelastic, so spending holds up even when income softens. Households will delay buying a car or upgrading their washing machine during a recession, but they rarely cancel a medical procedure or pull their kids out of college.

2. No inventory cycle to amplify shocks. Goods can be stockpiled, amplifying booms and busts while services cannot.

3. Limited exposure to global supply shocks. Most services don’t depend on imported inputs or energy-intensive production, so when global supply chains seize up, or oil prices surge, the pain is felt mostly in goods-producing industries.

4. Automatic stabilizers. Employment in the government, education, and health care sectors tends to remain stable or even rise during downturns.

Together, these features make service-sector employment inherently less volatile over the business cycle.

The Labor Market Is Structurally More Resilient Than in the Past

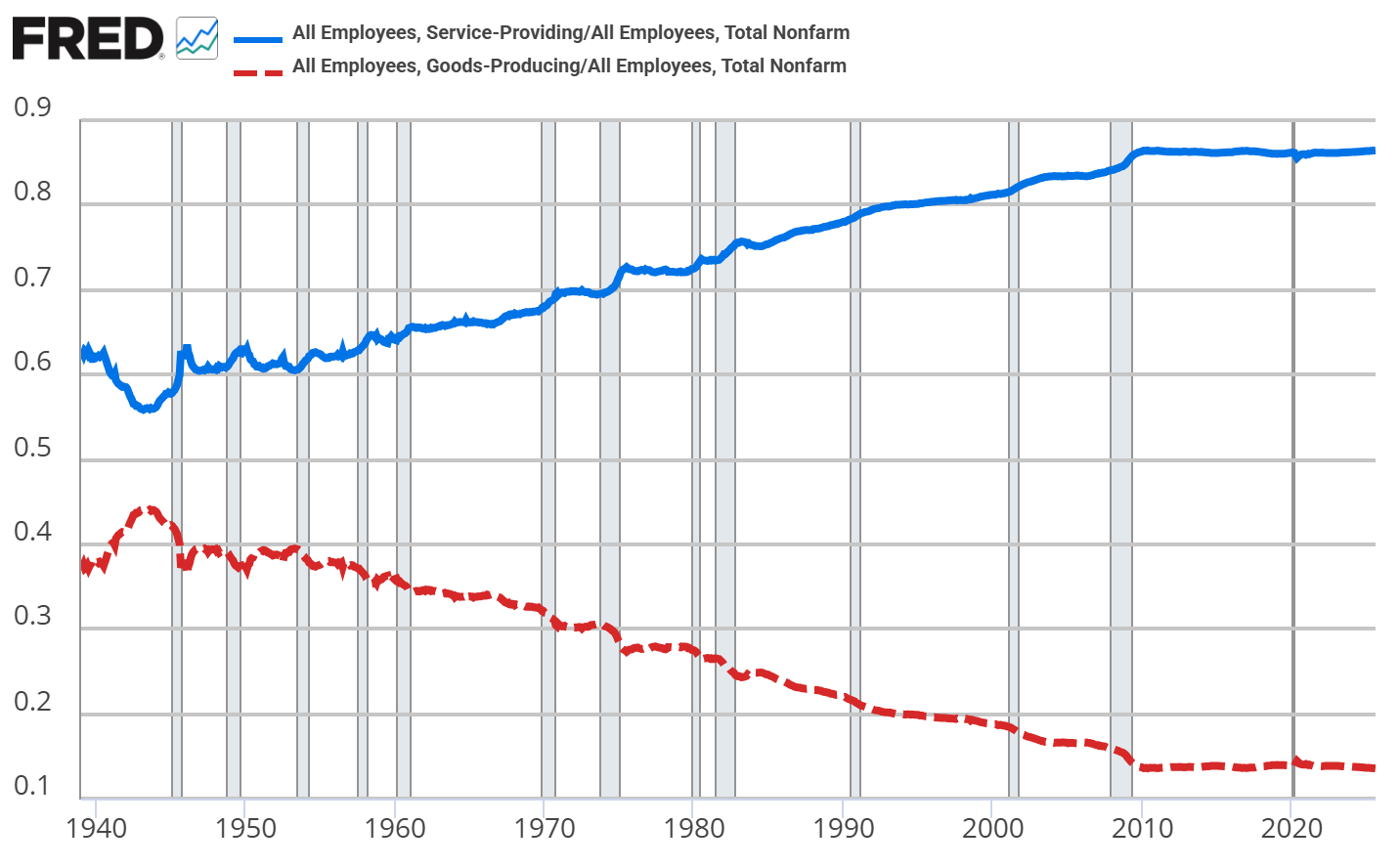

These sector-level differences only matter for the aggregate economy in proportion to each sector’s share of total employment. And as Figure 4 makes clear, the composition of employment changed dramatically between the mid-1950s and the late 2000s.

In the mid-1950s, roughly 62 percent of U.S. workers were employed in the service sector. By the late-2000s, this number had risen to about 86 percent. Conversely, goods-producing employment fell over this same period from nearly 40 percent of total employment in the mid-1950s to just 14 percent by the late-2000s.

The changing composition of the labor market toward less volatile service-providing industries means that the overall labor market exhibits smaller fluctuations when hit by a typical recessionary shock. Whereas prior to 1980, it was common for total employment to be pushed 2 percent or more below its long-run trend during recessions, since 1980 the only two times this threshold was breached were the financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 5).

This basic pattern is not new. Economists have documented many elements of this shift already.

Research by Davis and Kahn, for example, shows that part of the “Great Moderation” came from the U.S. quietly shifting away from volatile manufacturing and construction jobs toward steadier service-sector work. Other studies (e.g., Foerster, Sarte, and Watson [2011]) find that shocks to manufacturing used to drive recessions, but their impact has faded as the sector has shrunk. (If you’re curious, I’ve included a list of further reading at the end with more related academic articles.)

My argument pulls these strands of the literature together and pushes them one step further: because the most cyclical parts of the economy now make up a much smaller share of employment, it takes a much bigger, more system-wide shock to produce an actual recession. The mechanisms that used to generate recessions have weakened, making the economy structurally more resilient.

Today, to generate a broad‑based decline in employment, a shock must either:

(a) hit the service sector directly, or

(b) be severe enough to drag services down indirectly.

This is why typical supply shocks—like oil spikes in the 1970s—rarely trigger recessions today. It now takes something on the scale of a financial crisis or a global pandemic. This also helps explain why the recent Fed tightening cycle did not produce a recession.

Implications for Investors and Policy Makers

These structural changes don’t just alter which shocks are capable of generating a recession. They also have important implications for investors and policy makers:

Manufacturing revival vs. macro stability. Efforts to “re-industrialize” the economy may have political appeal, but a larger manufacturing base would also make the overall economy less resilient.

AI and sector‑specific bubbles. If today’s AI investment boom unwinds, the direct job losses would be small—information services account for less than 2 percent of total employment. The risk is that a bust could spill over into construction and equipment manufacturing, or if the market for collateralized debt tied to AI-related infrastructure sours.

Stock market valuations. A more resilient economy justifies higher equity valuations: if recessions are less frequent and require larger shocks, the risk premium investors demand falls, supporting higher stock prices.

Key Takeaway

The U.S. economy has become far less fragile than stock market fluctuations suggest. Investors may hang on every payroll report, treating routine month-to-month variations as signs that the labor market is cracking, but in a service-dominated economy that’s simply not how recessions form. Routine hiring slowdowns or modest increases in unemployment tell us very little about recession risk because it now takes a truly large, system-wide shock to make the labor market roll over. In short, the rise of service-sector employment has raised the threshold for recession. The economy isn’t immune to downturns, but it is more resilient and far harder to push into recession, than it used to be.

If you enjoyed this mildly efficient and occasionally rational take on how the rise of service-providing employment has made the economy more resilient, consider subscribing below. We’ll continue exploring markets and models, revealing mildly surprising truths.

No hot takes; just thoughtful ones.

About the Author: Seth Neumuller is an Associate Professor of Economics at Wellesley College where he teaches and conducts research in macroeconomics and finance. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from UCLA. His Substack is Mildly Efficient (and Occasionally Rational) where he explores topics in finance and macro from first principles, cutting through complexity with clear, grounded analysis.

Further Reading

If you’d like to explore the academic research behind this topic, here are some of the most relevant papers and a brief summary of their main findings:

• Davis & Kahn (2008), “Interpreting the Great Moderation.”

Shows that part of the decline in macroeconomic volatility since the mid-1980s reflects a shift away from highly cyclical industries like manufacturing and construction toward steadier service-producing sectors. This is one of the closest academic foundations for the argument in this piece.

• Foerster, Sarte & Watson (2011), “Sectoral Shocks and Aggregate Fluctuations.”

Finds that historically, goods-producing industries accounted for a disproportionately large share of aggregate volatility. As those sectors have shrunk, so has the impact of goods-sector shocks on the overall economy.

• Ariu, Kikkawa, Lange & Leduc (2020), “On the Resilience of Services During the Great Recession.”

Documents that service employment contracted far less than manufacturing during the Great Recession across advanced economies, highlighting the inherent stability of the service sector.

• Moro (2015), “Structural Change, Growth and Volatility.”

Shows that as economies evolve from agriculture → manufacturing → services, both output and employment volatility naturally decline.

• Stock & Watson (2002, 2003), “Has the Business Cycle Changed?”

While emphasizing improved monetary policy as part of the Great Moderation, they also note the role of structural factors, such as shifts in industry composition, in reducing volatility.

• Baily & Bosworth (2014), “The United States Economy: Why Such Slow Growth?”

Provides evidence that employment volatility has fallen significantly and that goods-producing industries were historically the main drivers of recessions.

• Ngai & Pissarides (2007), “Structural Change in a Multisector Model of Growth.”

A foundational model explaining why the service sector rises over time due to different productivity trends and income elasticities. While not directly about recessions, it underpins the long-run shifts discussed here.

• Fang & Rogerson (2011), “Productivity Shocks, Employment, and Hours in the U.S. Postwar Economy.”

Shows that employment volatility fell as economic activity shifted toward less-cyclical industries, consistent with the theme of this post.

These works collectively show that the composition of the economy matters enormously for how recessions unfold, an idea central to the argument here.

Notes and Sources

AI tools were used to edit prose; all figures are straightforward to reproduce from the cited sources.

According to the BLS, the confidence interval for the monthly change in total nonfarm

employment from the establishment survey is on the order of plus or minus 136,000. What this means in practice is that if the monthly estimate is +50,000, there is a 90 percent chance that the true change in monthly payrolls lies somewhere in the interval -86,000 to +186,000 (50,000 +/- 136,000). See https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.tn.htm for details.

Economists use the term “Great Moderation” to describe the multi-decade decline in the volatility of U.S. output and inflation beginning in the mid-1980s. Explanations typically include smaller economic shocks, improved monetary policy, and better inventory management. My focus here is different: how long-run changes in the composition of employment—from goods-producing to service-providing industries—alter the mechanics of recessions themselves.

The structral shift to service employment is fasinating, but I wonder if there's a downside we're missing. If services make the labor market more stable, does that also mean policy makers might underestimate risks until a truly catastophic shock hits? The resiliance could breed complacency in monitoring early warning signs that don't show up in monthy payroll data anymore.